18

The Pursuit

As usual the morning was busy, and the G.G.’s shiny barouche did not make much progress in the crush in the streets.

Welling stared blankly at the scene for a little, frowning, and then ventured: “I say, poor little thing, eh?”

“Miss Morgan? Yes. God knows what sort of a life she must lead. And she’s the determinedly nice sort—the sort that'll be Englishified if it kills ’em. Not that there’s any hope of a chee-chee being accepted within the Indian community. –Oh, sorry, Welling: that's a half-caste.”

“That right, sir? S’pose she was a funny colour, only—well, didn’t like to look at her, tell you the truth. The disfigurement, y’know. Dare say she feels it, too—didn’t look one in the face, did you notice, sir?”

He sighed. “Aye. Though if her mother is Indian, that is not surprising. Many Indian women live secluded lives, you know.”

“Aye, had heard that, sir.” He lapsed into silence, glaring into space.

The carriage of course was gone when they got to the place.

“They went off in that direction, according to Miss Morgan,” said Ponsonby grimly.

“Ye-es. That mean anything to you, sir?”

“Well, it ain’t the direction of his mother’s house!”

Poor Lord Welling gulped. “No,” he muttered.

“All we can do is try to trace them. This road carries straight on for quite a way, and the side streets are not fit for large vehicles. We may find someone reliable who noticed them.”

The young man looked at the bustling Indian street scene, and gulped. To his eye, no-one even looked respectable, let alone reliable.

“Look for a letter-writer.”

“Eh?” he groped.

Ponsonby smiled just a little. “Usually an older man, with a little writing desk, pen and ink, and so forth. Quite possibly squatting in the dust, but he may have a little stall.”

“Right you are, sir,” he said dazedly.

They drove on a little.

“Ah! Just a moment!” Ponsonby shouted to the driver and they pulled in. Lord Welling looked blankly at the shop before them: a typical small Indian store, all shop front, the wares on display to the dusty street, in this instance rolls and rolls of shiny silks, and the proprietor, in this instance a fat, greasy-looking fellow with an huge moustache, standing in what passed for a doorway, a gap between two huge piles of stuffs.

“He don’t look that reliable, sir!” he hissed.

“Nonsense, dear boy! I know him quite well: he is a respectable man, and always keeps an eye out for the carriage trade—of whatever colour!” he added with a smile as another carriage drew up and disgorged two Indian ladies in elaborately embroidered sarees of heavy silk, their wrists and, the fascinated Welling perceived, also their ankles, laden with gold jewellery.

He then got down and had an animated conversation with the man in the fellow’s own lingo. The two ladies, though pulling their sarees partly over their faces, joined in with vigour. Waving and pointing ensued, there were nods and bows all round, the Colonel shook hands heartily with the fellow—as far as Welling could see, no baksheesh even changing hands—and hopped back up, grinning.

“Not only spotted the carriage: spotted the English mem inside it, yellow hair, fancy hat!”

“Uh—you sure, sir? Well,” he muttered, reddening, “someone told me these Indian fellows will say what they think you wish to hear.”

“I am quite sure. I did not prompt him and in any case he has more sense than to lie to me. They turned left at the end of this street. Which I rather think means,” he noted grimly, “that he’s headed for that nice little bungalow that he’s reputed to have, about two days’ drive out.”

Welling looked at him in horror.

“Should have sent a man up there to keep a permanent check on the place, but I had no idea he was in serious pursuit of Josie,” he added grimly.

“I’ll kill him!” he choked.

Ponsonby Sahib patted his arm. “You won’t need to, dear boy, for if he’s laid a finger on her I’ll kill him myself. But I think we may catch him before nightfall.” He leant forward and shouted an order, and to Welling’s complete horror they turned right, not left, and set off as fast as was possible for the press of vehicles.

“I say, sir—!”

“Don’t panic,” said Ponsonby Sahib grimly. “We can’t take the G.-G.’s barouche out there—and in any case it ain’t fast enough. There’s a fellow lives not far from here who will lend us a decent pair of horses—and, in fact, probably force an armed escort on us to boot!”

The younger man sagged. “Good,” he said limply.

“And if we do catch them today, I’ll let you punch the living daylights out of Hatton, should you feel like it.”

“Feel like it!” he choked. After a few moments he met Ponsonby’s eye and grinned sheepishly. “Thanks, sir. Be my pleasure.”

Not unnaturally Welling expected Ponsonby’s acquaintance with the horses and the armed escort to be a military man. The carriage drew up before a high blank wall, a greyish shade that might once have been white. The tall wooden gate in it was closed. One of the Indian footmen up behind got down and rang the bell—he bore all the earmarks of a servant whose task was beneath him. What appeared to be an argument ensued, but as the Colonel remained unmoved, his Lordship tried not to panic. Than the gate was dragged open and they drove into a large, dusty courtyard. Before them was a tall white house with almost no windows, and those it had covered with unwelcoming grilles. Its large front door, however, looked more promising, in that it was very grand indeed: elaborately carved. It opened before anyone could knock, and two Indian servants appeared, bowing. They wore Indian dress but Welling was now used to this and he waited expectantly. The fellows at least looked clean, and their turbans were well starched. Probably the house belonged to some Calcutta nabob.

But the owner was not a wealthy Englishman of his own class. In fact he was not an Englishman at all. He was a giant, bearded Indian, well over six foot—Welling himself was very tall but this fellow overtopped him and was about twice as wide into the bargain. He wasn’t wearing a turban, just a funny little hat in what looked like white lace. The rest of his dress consisted of a long white shirt affair and baggy white pants, just like his servants’, but over his shirt he wore a black velvet sleeveless jacket, elaborately embroidered in gold and silver, the total effect being much enhanced by a wide black and silver fringed scarf tied round the enormous stomach. Into this sash, his Lordship perceived dazedly as the fellow moved, were stuck a pistol with an intricately chased gold handle and a giant curved dagger in a fancy scabbard, both scabbard and hilt adorned not merely with worked gold but with emeralds and rubies. Welling gulped, and gulped again as the man greeted Colonel Ponsonby like a long-lost brother—kissing him, in fact, on both cheeks! He was introduced, but Welling, to his embarrassment, didn’t quite get it. Something Khan, was it? He said: “Delighted to meet you, Mr Khan,” and this seemed to go down very well, thank goodness! The Colonel addressed him as “K.K.” but Welling didn’t feel he should.

Presumably explanations then took place, because Mr Khan shouted orders, fellows were sent running, and they were urged inside. Welling gaped around him. The English people he had met out here so far did live pretty well, but this place was a palace! They crossed an elaborate marble lobby, went through an even more elaborate marble room filled with low, silken couches, and emerged onto a tiled courtyard surrounded by elegant pillars, lacy stone arches, and innumerable little balconies, and crowded with palms, low seats, tables, elaborate vases, and glorious Oriental rugs. Into the bargain a fountain was plashing into a charming little pool.

“Pleasant, isn’t it?” said the Colonel with a smile.

“Wonderful,” he said dazedly.

“Mm, K.K. has beautiful taste. Sit down, Welling.”

Numbly his Lordship sank onto a low couch, realising as he did so that their host had vanished.

“K.K.’s decided to come with us—just getting changed into something fit to ride a horse in. Something he deems fit, at any rate!” added the Colonel with a grin.

Welling smiled weakly, and accepted a small cup of pitch-black coffee. Since the bowing and beaming servant was urging a trayful of stuff upon him—it was all in Indian but it was definitely urging—he took a small pink thing. Sweetmeat or some such.

Ponsonby Sahib watched in amusement as he bit into it and chewed, and an expression of astonishment came over his amiable blond face.

“What are they, sir?” he gasped as Ponsonby took one, too.

“They are a favourite Indian sweetmeat called ‘barfees’. These are just the usual ones.”

“Usual? I’ve never tasted anything half so good!”

He smiled. “Most Europeans either adore them or loathe them.”

“How could one possibly loathe them? They—they’re—indescribable!” he ended.

“Yes, I think so, too. It’s rosewater, Welling. We often have ’em at home.”

“They never served us up anything half so good in Bombay!” he said fervently.

Ponsonby beckoned to the servant, said something, and the man beamed and put his tray down on the low, short-legged table between them.

“Like the table, Welling?” he asked carelessly.

“Indeed, sir. Lacquer, isn’t it? Chinese work? –Aye. Curious, being so low, but very fine.”

“Exactly. I perceive,” he said with a twinkle in his eye, “that you are not a hidebound thinker.”

“Uh—most people would claim I don’t think at all, sir,” he admitted on a glum note.

“Most people,” drawled Ponsonby Sahib, “mean by that, that one does not think as they do, that is, that one does not think along hidebound lines. I’d ignore ’em. A man’s entitled to his own outlook upon the world. –Ah! Here is K.K.: I am sure he’ll agree.” He said something to their host and the giant man shook his head in a curious gesture and bowed to Welling.

“Every man must look upon the world in his own way, Lord Welling,” he said in a deep, rumbling voice.

Welling jumped. So far the man had not uttered a syllable of English!

“You are most welcome in my house. Please, have another barfee.”

“Thank you very much, Mr Khan. I was just saying to the Colonel, they’re the most wonderful tasting things I’ve ever eaten, sir!”

Mr Khan gave him a sharp look, saw he was perfectly genuine, and beamed upon him. “Ah! You like the rosewater! Bhai!” A bearer dashed up, was given a pithy order, and returned quickly with a bundle tied up in a silk scarf.

“Just some barfees,” said Mr Khan on a complacent note.

Welling accepted it dazedly. “Thank you. You’re very good, sir.”

“Not at all. Shall we go? The horses will be ready. Are you sure you don’t want camels, dear man?” asked Mr Khan, putting a hand on Ponsonby’s shoulder and steering him out.

“No, thanks, K.K. Don’t think Lord Welling has ever managed a camel.”

“Rather not, sir!” he gulped. “Been on an elephant, though. Didn’t like it all that much, to tell you the truth. Well, liked the elephant itself: seemed a very friendly beast. But they sway, don’t they? Felt a bit sick, almost as bad as the ship, really.”

“Then camels,” returned Mr Khan solemnly, “would not do, for they sway much more. But my camels are fast, and all camels are good stayers.”

“Your horses go like the wind, though,” said the Colonel with a smile, as Welling just gaped at what was now revealed in the outer courtyard.

Mr Khan was evidently very pleased, though he shook his head, spread his hands deprecatingly, and said: “They have been eating their heads off in the stable for weeks, dear boy. However, I dare say they will catch a hire carriage. Please, take the grey, Gil. Lord Welling, would you care for the chestnut?”

He himself then mounted onto the huge black. The feistiest-looking brute his Lordship had ever seen: the groom at its head was having his work cut out holding it. It was seventeen hands if an inch, and built like—well, the words “war horse” came to mind. Strong? Phew!

The grey was not half bad, either, a beautiful thing—a stallion, he realised, as the Colonel mounted onto its elaborate saddle. Glorious long white mane and tail, not plaited neatly in the English fashion, but looking as if they might have been braided and brushed out—rippling, that was the word.

His own mount, a glossy chestnut mare that would have looked completely at home in the Park, had been treated similarly, and to boot had flowers tucked into her bridle. He swallowed, but got up.

They had an armed escort, all right: two ferocious-looking fellows in turbans almost as large as the one which Mr Khan was now wearing, armed to the teeth. Rifles, pistols, and daggers. One of ’em had an extra dagger in his boot, and they both had bands of cartridges strapped across their chests. Oops—no, one fellow had one lot of cartridges and a belt with two extra daggers in it!

“I don’t think,” said Ponsonby detachedly as they set out, only to be immediately slowed by the press in the city street, “that Hatton is likely to make very much of a stand in the face of this little lot.”

“No,” agreed Welling feebly, as Mr Khan gave a loud, rumbling laugh. He then presumably translated for the escort: they laughed, too!

By the time they reached the outskirts of the busy city Welling had begun to feel despairingly that they’d never catch the cursed fellow, their progress had been so slow. But suddenly they were on a clear, dusty road, Mr Khan gave a shout, and they were off!

... We made good time on the road—K.K.’s horses, as you know, are the best in Calcutta—nay, I would dare swear, the best in India—and he favoured myself with the Arab stallion, Shah Jahan—the one a certain personage offered him a fortune for and was told he’d rather sell his wives, subsequently laughing in the fellow’s face—and Welling with a chestnut mare called Mumtaz. Goodness knows what colour the offspring will be, but they’ll be fast, I can guarantee it! K.K. himself was on Akbar, his great black. The sons, Allauddin and Aurangzeb, on almost equally fine mounts, Aurangzeb’s beautiful little chestnut a sister to Mumtaz, bred by himself, and Allauddin’s grey one of Shah Jahan’s get.

Well, as you will have gathered by this time, Jarvis, d— Hatton did not have a hope! Allauddin and Aurangzeb were quite ready to slit his throat—had already offered to, indeed; just as well Welling don’t bolo the baht, hey?

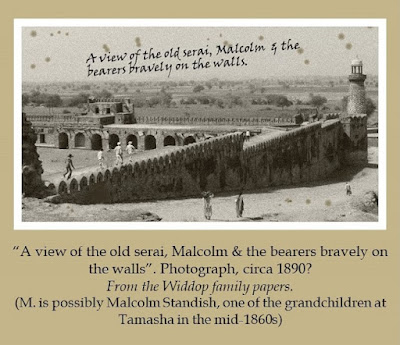

The stop at a typical serai to rest the horses and take some refreshment ourselves was something of a shock to W.’s system, but he bore up nobly. We were done very well indeed, and offered anything one could desire, from rooms for the night—fortunately no-one translated that, for he was already in a state of high anxiety—to a cooling bath. The others were only too glad to take advantage of the last offer, as was I—well, I have visited at a serai which had one of the noblest baths I have ever seen, and at others which had no bathing facilities except the usual pot of water, but this was not half bad, for its size. Welling, however, did not feel the need to wash, so after the others had gone out I explained that in India, contrary to popular English opinion, those who do not wash several times a day are considered filthy. He got the point without my having to mention that not washing would grossly insult K.K. and his boys—not as dim as some claim, you see! I warned him not to be surprised at any offers to pour the water, scrub the back, &c., and off we went. As you will guess, it was not a beautiful houri or a female of any sort, which I rather think he had been expecting, but a wizened little fellow who looked all of eighty years old, though the lack of teeth was helping, dare say he was only about fifty. As you will also guess, towels were not offered, but we could hear K.K. shouting, and very soon another fellow panted in with lengths of cotton cloth for us. Followed in short order by Allauddin with fresh clothes that they’d packed in the saddlebags. W. extremely taken aback, at this! The more so as yours truly got into the shirt and pyjama without remark.

However, he rallied—he has excellent bottom, just knows nothing whatsoever about the country he’s found himself in—and eventually even congratulated the proprietor on his “mutton curry”. Well, strictly speaking it was a biriyanee—delicious, too—and the meat was goat, but K.K. very kindly translated into both a language and a terminology the man would understand!

A Biriyanee of Meat (To Serve Ten)

Any red meat will do for this dish: in India it is generally mutton or lamb, but very suited also to goat. Fry 2 onions, sliced, in 2 tablespoonfuls of butter till coloured. Mix with 3/4 tablespoonful of coriander powder, 1 teaspoonful of turmerick, salt & 3/4 pint curd [yoghurt]. Rub well into 1 lb. of meat, cut in slices, and let stand 1/2 hour. Take 2 lbs. of cleaned rice, steep for 1/2 hour & rinse well. Parboil the rice. Pound 2 onions & combine with the meat. Cook without butter till it begins to dry. Layer all in a heavy casserole dish, topping with rice. Sprinkle with seeds of 2 elaychee [cardamom] pods, 1/2-inch stick cinnamon, 3 cloves and 1/2 teaspoon chilli powder. Pour over 4 tablespoonsful of melted butter. Splash with a few drops of water & hermetically seal the lid. Cook for 50-60 minutes. In India it is cooked on the coals but it may be done in a very low oven for 45 minutes. Then leave for 5-10 minutes.

Your guests will appreciate this decorated with halved hard-boiled eggs & sprinkled with a little rose water.

******

By this time we were all sitting around on the customary mats in the big communal area, with nearby another party, consisting of a camel trader—much yelling at his men to get the camels watered first, thoroughly good fellow!—his half-dozen assistants, largely his sons, I think, another half-dozen who seemed to be their party’s servants, three young boys who were the sons of some of the party, and a mountain of a matron, who had ridden in a kind of howdah on the largest camel, poor beast! The begum was very much not in seclusion, and ordered the group about like nobody’s business! Welling summed it up as quite an experience, and he never knew we had these giant “inns” with the huge courtyards, in India! Nobly I refrained from pointing out that camels are not small, and they have been an accustomed mode of transport here for hundreds of years. As also that no-one but an idiot would dream of leaving his camels or horses outside the walls, and unprotected! Oh, well, I knew as little when I first came out!

We were off again as soon as the horses had been checked and found to be satisfactory. Welling congratulated the Khans on the speed and stamina of their beautiful beasts, and lo and behold! Aurangzeb actually broke down and said to the fellow—in English, Jarvis, never heard him use it but to you or me!—“Thank you, sir. I breed these mares myself.” Welling nearly fell off Mumtaz, and to say truth I was not much better! Old K.K. was beaming upon us, tho’ I think he may have been as shocked as I, underneath! Well, yes, Aurangzeb is a considerable linguist, not to say scholar: he favoured me over the meal with a short dissertation upon one of the poems in Ancient Persian he is currently reading—I own I should like to see the MS., if it be anything like some of those K.K. owns! I fear I had much ado to grasp the bit he quoted for me, and he kindly translated it into first Arabic and then Urdoo, without any effort whatsoever. Moreover, tho’ my Arabic is not terribly good I did grasp that he used a poetic form! But to reveal to a stranger that he also speaks English? One can only conclude he both likes and approves of the man. Well, good seat on a horse, yes, but that has not influenced him heretofore!

At the next place we stopped to enquire they had definitely been seen, the mem having been spotted in the carriage, but they had not stopped—pithy remark on the quality of the nags poled up, with a rider to the effect that the English don’t understand horses. We were much encouraged and pressed on eagerly, not without anxious glances at the sky, for the sun was now observedly sinking. Aurangzeb’s little mare was freshest—wish she was mine, I have never seen such a fine little horse, Jarvis!—and he offered to press on ahead. Well, yes, dear man: God knew what he’d do if he found Hatton, but I agreed, and off he flew.

It was nearly dusk and Welling was visibly upset by the time he reappeared. They were up ahead at the next serai, and we were not to worry, for the young mem had slapped the yellow-haired villain upon his wicked face in full view of the innkeeper’s wife, and when he’d attempted to remonstrate, kicked him viciously in the shins—all present who could bolo the baht agreeing fervently that it should have been the goolies. So Aurangzeb weighed into it: told the man and his wife that the wicked yellow-haired one had kidnapped the innocent girl. The which was well supported by Josie’s bursting into copious floods of tears. The innkeeper was hesitating—it was Hatton who’d be shelling out the gelt, of course—but Aurangzeb distributed largesse and it was all over. The serai-keeper himself offered to tie the wicked kidnapper up until the lady’s relatives could deal with him appropriately, but Aurangzeb, first knocking the fellow down, was only too happy to perform that service. Of course Josie hadn’t understood a word, but she’d understood the actions all right, and cast herself upon poor A.’s bosom, sobbing. Just as well he is a man of both sense and sensibility, with a love of the romantic poetry of the East, for he merely patted her back and handed her over to the serai-keeper’s wife.

This lady led her out, to reappear in very short order with a large carving knife, offering to perform the office, but Aurangzeb assured her that the young lady’s English relatives were in hot pursuit of the monster and he would be subject to English law. “Not nearly enough!” was the cry from all present—a crowd had gathered by this time, as you have no doubt realised. But Aurangzeb calmed them down and rode off to us post-haste. He did admit there was no guarantee that the knife would not be used, the woman had fire in her eye, but for a man from his culture, he acted with extraordinary restraint.

I translated the salient points for Welling as we hastened on and he was most disappointed that he would not have the job of knocking the fellow flat after all: so I assured him—omitting the knife factor—that it would be our pleasure to lead the fellow outside, untie him, and let Welling do whatever he liked. K.K. and Aurangzeb agreeing loudly, and even Allauddin, whose English is not so good, loudly concurring. In fact he offered his very own knife to Welling! Seemed the ceremony was going to be performed one way or t’other! But luckily he did not grasp the full import of the offer.

It was unnecessary for Aurangzeb to point out the serai as they arrived: they could all see it. Nobody spoke: they all dismounted and, as the proprietor had dashed into the courtyard and was bowing and scraping—K.K.’s presence alone would have done it, Ponsonby Sahib rather thought, but Aurangzeb had undoubtedly put the fear of God into the fellow—they all followed him inside.

Charlie Hatton was lying on the floor, well trussed up. Aurangzeb went over to him and gave him a disdainful kick. Still nobody spoke. The fellow had been very red and flushed at first but when he realised who the fourth turbaned figure in shirt and baggy white pants was, he went a nasty greenish colour.

Finally Ponsonby said: “Take his gag off, would you, Aurangzeb, my friend? Let’s see if he has anything to say for himself.” –Not in English. Hatton, of course, did not understand a word, in spite of having lived in the country for all of his childhood, and merely glared.

Aurangzeb shrugged but removed the gag.

“Well, go on!” said Welling angrily before anyone else could speak. “Try and justify yourself, you filthy little rat!” –Not elegant, but clear. Allauddin and Aurangzeb exchanged glances, and nodded pleasedly.

Charlie glared. “Who the Devil are you?”

“Nemesis in correct English morning wear,” drawled Ponsonby Sahib. “Do you have anything to say for yourself before we mete out justice?”

“Yes! She came of her own accord!” he spat.

Obligingly Aurangzeb translated this into Bengalee for his older brother. Allauddin smiled grimly and withdrew the knife from his boot, fingering it lovingly.

“I did not! He tricked me!” cried a shrill voice. And Josie rushed in, tear-stained and hatless, and threw herself at her guardian.

“She got into the carriage of her own accord! She’s been leading me on for months! And if you let these heathens lay a finger on me, Colonel, you are as bad as they are!” spat Charlie.

Allauddin must have understood this: he shouted: “Liar!” in Bengalee, and “Death to the unbeliever!” in the language of the Holy Book—and raised the knife.

“No, it’s all right, he only meant you are not Christians,” said Ponsonby hastily in Bengalee.

“Yes,” agreed K.K. in English. “Stupid as well as venal, one must conclude, my dear Gil.”

“Quite.”

“And a liar!” gasped Josie, ceasing to sob all over Ponsonby’s chest.

“We’ve known that for some time, Josie. Not that it will affect our actions one way or t’other, but why did you go with him, unaccompanied?” he returned calmly.

Josie glared resentfully at Charlie. “He told me a string of untruths, that’s why, Ponsonby Sahib! I thought we were merely going on a picknick with Diane Fanshawe and Mr Yelby!”

Young Yelby was all of nineteen. Ponsonby could not recall which of Fanshawe’s girls Diane was, but if she was a friend of Josie’s, presumably the silliest. “Under whose escort?” he asked without heat.

Josie reddened, and pouted. “Wuh-well, nobody’s, sir, but—but it was harmless! At least, the way he phrased it, the horrid liar! He said it would be fun! But we drove for miles and miles, and there were no temple ruins, and then we passed a serai and I said why not stop, we must be lost, and he just smiled and said it was not so very far to his horrid house, and as we seemed to have gone astray, we had best make for it—and—and it was all lies!” she wailed, bursting into renewed sobs.

K.K. was translating for Allauddin. Ponsonby just patted her back and waited until he’d finished, though he was aware that Welling, who had turned purple, was fuming.

“I see. The whole thing was a trick, then, my dear. Don’t cry, you’re quite safe now. Well, shall we let Lord Welling finish him off?” he suggested calmly.

“Yes!” she said viciously, ceasing to cry and looking up eagerly.

“Why not?” agreed K.K.

Charlie looked greener than ever but he shouted: “My father will have the law on you!”

“Yes? If this is Major Hatton, I rather think he will shake our hands,” returned K.K., unmoved. “Take the scoundrel outside, my sons.”

And Charlie was duly dragged out into the courtyard.

It was now dark—night falls quickly in those climes—and the serai-keeper, all agog, hurried out with a flaming torch. Followed closely by his more practical wife with a feringhee-style lantern and—oops!—the carving knife again.

Swiftly the Khan brothers untrussed him, Allauddin getting in a kick as they did so.

“May I take your coat, sir?” said K.K. smoothly to Welling.

“Thanks very much, Mr Khan,” he agreed, stripping it off. –Now distinctly the worse for wear, and those pantaloons would never be the same again—doubtless from Mr Weston or some such eminent London tailor, and if their creator could have seen them now he'd probably have wept. The shirt was good: the clean one that he’d been given earlier. Though the dandy waistcoat was his own.

“All right, get up and fight, you scoundrel!”

An expression of unalloyed relief spread over Hatton’s face as it dawned he was not to be afforded local justice after all. He got up eagerly and bored in.

No-one offered a bet, unusual though this was: it was only too evident that nothing would stop Welling. And as he was both taller and heavier, the thing seemed a foregone conclusion. And so it proved. Hatton fought valiantly enough but he didn’t last long. Welling, who had little science, took a few blows to the upper body, and several kicks in the shins, but the outcome was never in doubt. Hatton finally went down from an almighty right to the jaw.

Welling stood over him, panting. “Get up, you filthy swine! You ain’t dead yet!”

“Why doesn’t he get up?” said Allauddin to his father in confusion.

“Because he’s a cowardly dog. –I am saying, my dear Miss Josie,” he said with immense courtesy, “that the man does not get up because he is a cowardly dog. Or I think you would say rat, in English.”

“Yes!” agreed Josie fiercely.—She had not hesitated to cheer Welling on shrilly during the proceedings.—“Get up, you cowardly little rat, and let him kill you!” she shrieked.

The brothers understood this: they nodded approval.

Welling was still panting. “Think—he’s had—enough!”

Excitedly the innkeeper’s wife offered to cut ’em off for them!

“No,” said Ponsonby quickly before any of the Khans could encourage her. “He is subject to English law. He will be judged and thrown into the big jail in Calcutta.”

“Ah! Where he’ll die like a dog in the dungeons!”

“Yes.”

“Good!” she said viciously.

“Perhaps you could see about a nourishing supper for us?” he asked politely.

Beaming, she assured the sahib that it would be the best supper he had ever tasted, added admiringly that one would never know from the way the sahib spoke that he was not from Bengal, and hurried inside. With a parting kick, since the villain was still just lying there.

“That hit home,” said Ponsonby pleasedly as Hatton gave a howl and doubled up, clutching his privates.

“I say!” gulped Welling.

He gave in to temptation. “My dear boy, the alternative was to let her cut ’em off: what do you imagine the knife was for?”

The two feringhees present gaped at him. Faintly Josie ventured: “She was cutting up onions earlier.”

“No doubt. Nevertheless.”

She took a deep breath. “Well, if she had, I am sure it would have served him out! –Shall you prosecute him, sir?” she added eagerly.

“Josie, my dear, much though I should like to, it would cause the most terrific scandal. And the filthy little fellow would claim you came willingly, you know.”

Welling cleared his throat. “Aye. Best hush it up. Perhaps speak to his father, though, sir?”

“Mm, I think I shall.”

He glared at his fallen foe. “Wish we could drag him through the courts, though.”

“Well, for my part,” cried Josie, tossing the golden curls, “I should not care an you did! And I do not give a fig what anyone says of me, I know I was tricked! And our dear guardian believes me, that is enough for me! –I cannot thank you enough for coming to rescue me, dearest Ponsonby Sahib,” she added with tears in her eyes. “And you, Lord Welling. You were wo—huh—honderful!” With this she burst into sobs all over again.

Welling looked helplessly at Ponsonby.

“She is a bawler, you know,” he said mildly, hugging her. “Hush, Josie, my dear, it’s all over. We’ll tie him up and—uh—he ain’t getting one of K.K.’s horses. We’ll hire a mule from the man here, and take him back to Calcutta.”

“Personally I'd leave him, the miserable rat,” noted Welling.

“Er—mm. I’m tempted. But the woman would be out here with the knife before one could say—er—‘knife’.”

The Khans all got this, and collapsed in roars of laughter. Then coming to pat Welling enthusiastically on the back, and in K.K.’s case envelop him in a huge hug, congratulating him on his victory.

He emerged red but grinning. “Right-ho, then: tie him up, shall we? I say, Aladdin, have you got some rope?”

Unmoved at being thus addressed, Allauddin beamed, took his arm and hurried him off in quest of rope—though the scholarly Aurangzeb coughed suddenly.

“Now, I think we should go inside and have a wash before supper, mm?” suggested K.K.

“Yes, of course, dear sir!” beamed Josie, mopping her eyes with Ponsonby’s handkerchief. “I beg your pardon, but I do not know your name.”

He bowed. “K.K. Khan, Miss Josie. I am an old friend of your Ponsonby Sahib.”

“I’m delighted to meet you, Mr Khan, and thank you so much for coming with him,” she smiled. “Oh! But of course! You must be Tiddy’s Mr Khan!” She beamed at him. “The man with the camel train!”

Unmoved, K.K., who owned thousands of camels, trading all over the East, returned smoothly: “Of course; I have many camels, Miss Josie. When she was a little girl, Miss Tiddy would often come to see the kafilahs set off.”

“Yes, I remember! She said you used to travel all the way along the Grand Trunk Road.” She sighed. “Would that not be Romantick?”

“Indeed, Miss. A great adventure,” he agreed solemnly, shepherding them inside.

... Well, yes, dear man: flies, dirt and endless dust, not to mention the succession of budmushes one encounters along with the great number of genuinely good, solid, hardworking people! However, Aurangzeb and I also agreed politely that the Grand Trunk Road must be Romantick, and all was harmony. Well, Josie could not pronounce his name, but as no-one had expected her to, this did not signify! And we duly washed, Welling noting that he saw: they did do it a lot, but it was necessary in the climate. And adding that he had been quite surprised when the fellows unrolled their mats and did their kneeling stuff, but it took all sorts, and they were the most decent fellows he had ever met, and—the accolade—his Cousin Giles (Rockingham, that is) would like them. He did not express his even greater surprise at my having also unrolled the mat, but then he did not need to! No, well, K.K. expects it, and why not?

And so we sat down to a delicious supper consisting of a rice pullow (“Funny how these Indian fellows call their savoury dishes a pillow, ain’t it?”), a great pot of dal (“Thought that was only for breakfast, actually”), bowls of saag (“Never really liked spinach at home, y’know, but she’s done something miraculous to it!”—myself not breathing the words “mustard leaves”), of kela curry (he did not ask, so no-one informed him that this was banana, and he lapped it up like a lamb), of aloo mashla (“You'd never think they was potatoes, sir!”—how true), and of begoon, simply fried in the Bengalee way (“Looks funny, sir, what is it? –Oh. –Oh!”—having tasted.—“I say, delicious! Melts in the mouth!”) No, well, his heart’s in the right place, and so, it appears, are the taste buds!

Aloo Mashla (Whole Fried Potatoes)

Take 15-16 rather small potatoes, well cleaned. Boil them and then skin them. In a moderately hot pan, fry 2 tablespoonfuls of chopped garlic in oil, stirring. Add 3 tablespoonfuls of chopped ginger & 1 of chopped green chilli. Fry for a little, stirring. Add 1 teaspoonful of turmerick powder. Next add the potatoes with salt, & mix well to coat with spices. Fry for about 10 minutes till the potatoes become golden and get crusty crumbs around. These are enjoyable with a dish of curd and a chutney.

~~~~~

Begoon Bhaja

Very tasty and easy to prepare. 1 good-sized vegetable will serve 2 or 3 persons.

Take your begoon [eggplant], cut in round slices. Then sprinkle with turmerick powder & salt to taste. Rub well in & turn to marinate. Heat your oil (mustard oil is preferable) & when hot, lay in the slices, with 2 green chillis if liked. Cover the pan for a few minutes. Raise cover & turn the pieces. Lower the heat. Fry, turning, till the slices are nicely browned.

Naturally there were innumerable little side dishes, the woman putting her best foot forward—small sweet onions soaked in a mild tamarind solution, no-one disabusing Welling of his notion it was flavoured vinegar, a heart-shakingly hot pickle of chillies which Allauddin, bless him, only just stopped him eating in time, a selection of vegetable pukkorahs—myself, you understand, waiting for it to dawn that this was a meal for those who do not eat meat—a kasundee of raw green mangoes, also hot and salty, but not so hot, so he was allowed to try it—the eyes watering horribly, poor fellow! There were two curd dishes, doubtless in our honour. The pumpkin raita no doubt struck the unaccustomed palate as odd, not to say the colour, and he left it severely alone until Allauddin spooned some up for him. Unusual—quite! He did not know what to do with the plain curd, either, though identifying it as the same what we had for breakfast—it seemed like a lifetime back, Jarvis, as no doubt you can imagine! So K.K. explained very politely that in India there are many dishes that are eaten at any time of day. Personally, I could not have done it without losing my gravity. Reaction, I suppose. —No, dear man, it never dawned, in fact I doubt that he even noticed the absence of meat!

Josie had naturally been confined to the female quarters, the serai-keeper’s wife having taken her under her wing. Thank God she grew up in the country: she did not kick up a fuss, but accepted it as quite the accustomed thing.

And that was pretty much that. Next morning we commandeered Hatton’s carriage to take Josie home—I had forgot, in the stress of the moment, that it must still be there. However, the mule proposal had proven so popular with everybody that I did not dare to suggest we merely load the fellow onto the roof. So Aurangzeb in person selected a mule, kindly explaining to the mystified proprietor that although a camel was of course much better, he felt the mule would give the budmush a much more uncomfortable journey—roars of laughter all round. Hatton was ignominiously strapped on, his hands tightly bound behind his back, the mule was ignominiously roped to the carriage, not to one of K.K.’s beautiful steeds, and off we set for home.

Next chapter:

https://tamasha-aregencynovel.blogspot.com/2024/02/another-turn-of-wheel.html

No comments:

Post a Comment