3

Early Days In Calcutta

From the unfinished MS., circa 1899: Our India Days, Chapter 3

That’s right, children, sit down. How lovely to see you, Madeleine—and you have brought your brother, too? You are very welcome, Mr Thomas, but are you sure you wish to listen to the tales we tell the little ones? That’s very flattering, but if you are bored, you must not feel obliged to stay! –Yes, Tessa, sit on your great-aunty’s knee, that’s right! Gil, dear, if you do not wish to sit nicely on the pouffe, go to— No, Antoinette is writing, dear, she cannot have you on her lap. Thank you, Madeleine: but he may W,R,I,G,G,L,E, you know!

Now, today Antoinette has expressed a wish to hear more about Ponsonby Sahib’s early days in India and how he met Great-Grandpapa Lucas, so you little ones must sit quietly. No, no elephants today, Tessa, but if you are very good, there will be an iced cake for tea!

Doubtless Mr Thomas went to an excellent school, Matt, dear, but now is not the time nor the place— You must forgive him, Mr Thomas: his cousins are at Winchester or Harrow and his Papa has decided upon Rugby for him, so— Yes, an excellent school! There: you see, Matt? And your Papa went there! Your Grandpapa? Well, yes, because one sends one’s sons— Your Great-Grandpapa Lucas? Dearest boy, you have it all completely wrong! Our Papa never went to school! He worked for his living since he was a boy scarce more than your age, and was proud of it to the day he died! And so are we all! –Thank you, Mr Thomas: the whole world—or very nearly the whole world!—does drink Lucas & Pointer’s tea, and, indeed, the ships of the Lucas Line are seen all around the world! One does not amass a great fortune in this modern age, Matt, dear boy, by sitting at home in a pleasant country house like your Papa’s. And most certainly not back in those days! Oh, dear, where were we? Oh, yes:

In the year 1798, when Gilbert Ponsonby was a wet-behind-the-ears subaltern in Calcutta, he saved a man’s life. It all happened very quickly, in a dark alley, and the fact that they both escaped with their lives was not, really, due to any conscious gallantry on the young man’s part, but merely to quick reactions on hearing a scuffle and a cry for help. He was armed: in fact he was in full dress uniform, though not expecting ever to have to use the sword. The stiff training of the regiment, however, meant he had the weapon in his hand before he knew he had even moved. The two assailants were armed only with short knives: one quickly fell under his blade and the other fled.

—Yes, indeed, Matt, the very sword which sits above your Grandpapa’s desk to this day! High up on the wall, yes, Gil, and we do not touch it. –You do not have it quite correct, Mr Thomas: as a very young man, Ponsonby Sahib was merely an average swordsman. It was later that he developed his skill with a blade—yes, and as Tiddy says, with a knife as well as a sword! Yes, indeed, Matt: in his day he used all those wicked-looking Indian blades in the cases in the study. –Locked, Gil baba, yes, and we do not touch, do we? That’s a good boy! –Yes, of course you wish to know who the man was, Antoinette, and that is the point of the story!

The man whose life Ponsonby had saved was nothing very much: one of those earnest scrapers in the gutters of commerce to whom the regiment referred with a kind of semi-tolerant scorn as “box-wallahs.” He insisted on knowing his rescuer’s name, forthwith begging to introduce himself: Henry John Lucas, very much at his service and his obliged servant for life. In the month that followed he embarrassed Ponsonby horridly by turning up at inconvenient moments with little gifts for him, ranging from bottles of frightful scent purchased in the bazaar, to curious artefacts such as a tobacco pouch of crocodile skin, an elephant’s foot umbrella stand large enough to have graced the front hall of the burra bungalow itself, and a brass native goddess with six arms.

Followed by, oh dear, a living, breathing native goddess with flowers in her hair! In the burra-sahib’s outer office on a day on which the General was expected to visit!

Very fortunately the sergeant on duty with Sub-Lieutenant Ponsonby in the outer office was more than capable of dispatching half a dozen chee-chees with flowers in their hair about their business and did so, ekdum! Advising the bowing and perspiring Mr Lucas that even though Mr Ponsonby might have saved his life, it was not the done thing for mulaquati and such-like to hang about the sadar with offerings for junior officers. After that Mr Lucas confined himself to humble chitties begging the Lieutenant to honour him with his company for a chota peg, or a chota dinner, etcetera. Ponsonby sometimes went: there was not all that much variety in the social life of Calcutta. Of course, being a pretty typical example of a healthy young Englishmen of the upper classes, he patronised poor Mr Lucas unmercifully as he did it. And once he had shaken the dust of the place off his boots and was off northwards with the regiment, allowed him to go completely out of his mind.

—No, well, that was how things were in those days. The officers of an English regiment would think themselves very much above a mere box-wallah. No, they don’t necessarily have boxes, Gil, darling. An elephant’s foot just like the one in the hall of our dear Tamasha, Tessa? But of course: it is the very foot! Shot with an elephant gun, Matt? Possibly, dear, but more likely it had just died of old age. Very old, Tessa, elephants live to a great age. Older than Grandpapa? Very likely. Now hush, and you will hear how the two became fast friends!

Quite some years passed before an older and wiser Gil Ponsonby—yes, a Gil just like you, Gil baba: hush, now, and listen—before Gil Ponsonby found himself back in Calcutta, after many and varied duties and a very great deal of experience of men, good, bad and indifferent, and of every class and caste of society, high or low, black, white or in between, that strove and struggled for King, country, the Company, their families, or just simply for breathing space, upon the vast sub-continent. And it was only at that point that Ponsonby said guiltily to himself: “I wonder what became of poor old Lucas? He was not a bad fellow, by any means. And I never so much as wrote him a chit to ask how he was getting on.”

He forthwith made it his business to discover what had become of Mr Lucas. Inquiry in the old haunts producing nothing at all—many of the old haunts, indeed, having been torn down in the interim—he broadened his search into the wider commercial scene of the thriving city, and was astounded to discover Mr Lucas living in the greatest comfort imaginable in a positive palace, in the very best area of town! Those ten years that had turned the self-centred, heedless young subaltern into a determined, hard, and very cunning officer had seen Mr Lucas become a positive nabob. Possibly the adage that unto him who hath it shall be given had some truth in it, for after marrying a rich man’s daughter while he was still making his own fortune, he had subsequently inherited the father’s business. Calcutta was a city which contained, alongside the poorest of the poor, some very wealthy men indeed; but Henry John Lucas was certainly one of the richest in it.

In fact he was so rich that Gil Ponsonby felt considerable hesitation about thrusting himself upon his notice; and eventually merely left a card.

Two days later Lieutenant-Colonel Wynton, Captain Ponsonby and Dr Little, chatting companionably in the officers’ mess over pre-dinner drinks, were extremely startled to have a salaaming servant inform them in an awed whisper that Mr Lucas had called and would be grateful for a word with the Captain Sahib.

“Not Henry Lucas?” said Dr Little, staring.

“It is so, huzzoor.”

“Didn’t know you knew him, Gil,” said the doctor.

“I used to know him, yes. I had best see him, if you fellows don’t mind.”

“Show him in, ekdum, and don’t call the Doctor Sahib huzzoor,” ordered Lieutenant-Colonel Wynton.

Calling Colonel Wynton huzzoor instead, the man salaamed deeply and almost crawled out.

“Lor’!” said the doctor with a robust laugh. “Your stock will have gone up no end with the bhais, Gil! Henry Lucas is the most frightful swell. They say that Mrs General Hayworth’s been trying to throw that horse-faced gal of hers at him—the wife died last year, y’know.”

“No, I didn’t know. I’m very sorry to hear it.” Ponsonby got up rather limply as the servant returned—salaaming profoundly once more—with a very gentlemanly-looking portly man approaching his mid-years. “Mr Lucas: how very nice to see you after all these years.”

“The pleasure is all mine, Captain Ponsonby,” returned Mr Lucas, beaming, and wringing his hand. “You’re looking well, sir. Permit me to say I would never have recognised you.”

Gil Ponsonby would have recognised him anywhere: he was much plumper and much sleeker, and very, very much better dressed: but apart from that, he appeared the same eager-to-please, unpretentious fellow he had known ten years since. The which he could scarcely be. Not at that address, and with that reputation amongst his fellow merchants! Had he been mistaken in Lucas all along? Somewhat limply Captain Ponsonby introduced his companions and asked the merchant to sit down.

Mr Lucas did so, noting cheerfully that he had never been to the mess before. Colonel Wynton politely suggested that he might care to dine with them, in that case? Though he should warn him the food would be nothing like what he was used to.

Smiling, Mr Lucas accepted the invitation happily. “And I dessay you don’t know what food I’m used to, Colonel!” he added with a chuckle.

“No, but I would bet my commission that it cannot be anything like the travesty of a white soup that our boys serve up,” returned Jarvis Wynton composedly.

“I remember,” said Ponsonby, clearing his throat, “that you used to be very fond of the native food, Mr Lucas.”

“That’s right, sir: always did have a taste for it. And I remember,” said the merchant, apparently innocently, “that you never did have a taste for it. Would you have developed one, since?”

Ponsonby took a deep breath. There was a sight more to Lucas than met the eye, clearly—or than had ever met his innocent eye, at the age of eighteen. “I think you may have heard, Mr Lucas, that I have had to.”

Mr Lucas produced a case of cigars. “These are not half bad, if you gentlemen would care to? –This is only calf, not crocodile,” he noted to the ambient air, as a bearer hurried to light the cigars for the gentlemen. “No, well, what I heard was that a Señor Morano in Delhi was used to entertain lavishly in the native style. And also that he was probably not Spanish. Then there was a certain Pathan that came down with a camel train all the way from Dehradoon, at least that was what was said, and acted as cook for some time for a Mr Knowles. Shortly before Mr Knowles was clapped up for spying for the French. –Thank you, bhai,” he said as the bearer lit his cigar. He drew on it slowly and eyed Ponsonby blandly.

—Exactly, Matt: they were both Ponsonby Sahib! No, hush, Tessa, darling, your cousin is quite right. He dressed up and pretended to be those persons in order to catch the bad men, you see? By that time he had learned several of the Indian languages, and as well he spoke several European languages: he had ever an ear for languages. A Pathan is a man from the north, Matt. Usually very fierce. Indeed, Mr Thomas: bearded. Mm, on his chin, Gil, darling! Yes, must he not have looked funny? There are some pictures in the big books of men like that, yes, and we shall look at them any time you please. –Certainly you may see them, Mr Thomas, and you too, Madeleine, dear, if you’re interested. There are Tonie’s own sketches, and some charming Indian miniature paintings that Ponsonby Sahib collected, and a whole album of delightful sketches of life and customs in the mofussil that Tess was given upon her engagement to be married. Also our dearest Stepmamma’s drawings of the Indians in their native dress which she did for Josie baba and Tiddy baba when they were little girls, and the very special drawings of Indian animals which Ponsonby Sahib did himself to amuse a little boy who died. No, we did not know him, darlings. It was very sad, yes, Tessa, but these things happen, and the Indian climate is not kind to the baba-log.

But goodness, we are losing the thread! This was way back at the time when England was at war in the Peninsula with the French, children—quite some time before Waterloo, Matt, dear—and so you see, any Spaniard or Frenchman would have been highly suspect and so would anyone who had anything to do with them. Now, where were we? Oh, yes: the gentlemen in the mess!

Dr Little had turned purple at Mr Lucas’s revelations and was choking slightly. Colonel Wynton, however, preserved his calm. “You are very well informed, sir,” he said mildly.

“A successful businessman needs to be,” replied Mr Lucas unemotionally. “Added to which, I suppose I took an interest, in this instance.”

“Yes, well, you are perfectly correct, and I have developed a taste for, and considerable ability with, several of the native styles of cuisine,” Ponsonby admitted somewhat limply.

Mr Lucas expelled a stream of smoke. “You must have, yes, if you can recognise that there is more than one style.”

“Let alone call them cuisine,” noted Jarvis Wynton, as unemotional as the merchant himself. “May I congratulate you on your cigars, Mr Lucas?”

“Thank you. I have them shipped from Spain. Not easy, these days,” he said blandly.

“Surely you don’t trade with the Spaniards?” gasped Dr Little, taken unawares.

“Of course not, Doctor. Nor with the Frogs, neither. Though if you would care to honour me by dining at my house on Friday week, I can promise you a decent drop of Burgundy.”

Given, amongst other points, that the good doctor was known in Calcutta for his partiality for a decent Burgundy, this left them all with very little to say. The which Gil Ponsonby was in no doubt at all was very much Mr Lucas’s intention!

—Er, no, possibly you don’t see why Mr Thomas is laughing, Matt. Burgundy is a French wine, dear, and when England was at war with Boney we were not supposed to buy French wines. You would not like it, Tessa, darling: very strong and not sweet at all, nothing like our delicious Indian drinks! Yes, your great-aunties love the pink sherbet drink, too! Yes, Matt, your Papa drinks Burgundy, that is perfectly acceptable now. Shall we go on? The rosewater pudding with the dumplings, Tessa, dear? Oh, dear, do you remember that? The thing is, none of your mammas care for us to offer you children so much sugar— Very sweet, Madeleine. Far too sweet for modern English tastes, and we had really best get off the subject!

Sweet Dumplings in Rose Water Syrup

Heat 4 cups of milk to boiling & add the juice of 2 lemons to curdle. When completely curdled pour into a muslin bag & allow to drain. Press the bag with a weight & leave to drain further. Once the solid Cheese is formed, add 1 tablespoon of flour & knead to a soft dough. Form into small balls. Boil 1 cup of sugar & 2 of water together for 5 minutes to make a syrup & carefully drop in the balls. Cook them gently in the syrup for fifteen minutes. Cool & add 1 tablespoon of Rose water. To be served cold in the syrup.

Later that evening, as he escorted the merchant to his carriage, Ponsonby Sahib said frankly: “I think I owe you several grovelling apologies, Mr Lucas. Will you forgive me?”

“What, for being young and not seeing that a box-wallah in a frightful waistcoat what didn’t know the correct knives and forks any more than he knew how to talk like all you young gents in the chummery might nevertheless have a few brains? Even if he couldn’t figure out a way to make you see ’em? Don’t think I need to, do I?” he said mildly.

“Nevertheless I would be very grateful to know you don’t bear me a grudge, sir,” said Ponsonby stiffly.

“No, I don’t. S’pose I could, but then, you did save my life. And if a fellow can’t be callous and heedless at eighteen, when can he?”

Gil Ponsonby returned on a dry note: “I’ll wager you were neither, at eighteen, Mr Lucas.”

Mr Lucas laughed suddenly, and patted his shoulder. “Care to hop in, drive a way? No, well,” he said as the two seated themselves in the carriage and it moved off, “when I was eighteen I was already out here, working for Pointer’s. –Come out when I was sixteen, never knew there was so many black faces in the world. Bawled for me Ma every night for six months. At eighteen, I was stupid enough to tell old Pointer to his face that the way the warehouses were organised was not efficient. That’s a bit like telling your burra-sahib that he don’t know how to carry out a raid into enemy territory,” he explained kindly.

“Yes,” said Ponsonby meekly.

“Aye,” said the merchant with a little sigh. “Aye. Well, he didn’t sack me, though the whole office expected it. Instead he asked me, straight-faced as nothing, to write him out a report on what I thought should be done, and bring it to him at his house, ten a.m. sharp, two days later. –I sweated blood,” he said, shaking his head. “I was all right with figures, but had never writ more than half a line of words together in me life. You know: ‘item, 5 doz. linen handkerchiefs’: that sort of thing. When I got there it was like nothing I’d ever seen. Bearers everywhere, marble pillars, a great marble floor with pictures in it—Italian, from a villa near Siena,” he said, relapsing into his current persona. “He was an extravagant old devil, was Pointer, and had had every stone numbered, shipped out, and re-laid. I was made to sit on a gilt chair next to a great long-case clock, and kick me heels for forty-seven minutes by the said clock. Then he had me in, and made me stand there like a dummy while he read the thing through. After that he told me to sit down, called for chai—spoke three Indian languages like a native, he did, not that he ever let on that he could, except to one or two what was closest to him—and tore every word of the report to shreds. I was too young and thick to see that the fact that he was bothering to do so at all meant he thought there was something in me, and nigh burst into tears. Hardly took in a word he said, at the time—though later it all came back to me, and I realised I’d been listening to one of the finest analytical minds of our times. Well, I thought it was all up with me, and couldn’t swallow a bite, though he had a great tray of assorted samosahs and pukkorahs brought in special. With six different-coloured pickles, I can see ’em clearer than I see you. Then he said I had best go into the Calcutta main office for a while. Me ears sort of buzzed and I couldn’t speak. –Dunno if there would be a comparison in the military life,” he said, scratching his chin. “Maybe if the burra-sahib was to tell you he was putting you up for a promotion when you were expecting to be confined to barracks for the next three months, eh?”

“Officers are not generally conf— You know that,” said Gil Ponsonby limply. “I see.”

“Which was where I was when I met you,” said Mr Lucas blandly. “Mind you, I’d had a spell in Head Office in London, by then, and had gone up several steps. But we was all box-wallahs to a young gent straight out from Home, out of course.”

“Mm. I can only apologise. I was a young brute,” said Ponsonby remorsefully.

“Well, a bit blind, I suppose. Frankly I was surprised to hear you came through that first campaign.”

“Yes; I was d— lucky to be with Wynton,” said Ponsonby, clearing his throat.

“So they tell me—aye.” Mr Lucas stared blankly at the still-bustling streets through which they were passing. Eventually he said on an odd note: “Ketteridge was your Colonel, then, I think?”

“Yes, a splendid officer. –Terrifying, though! As much as your Mr Pointer, I think!”

“Mm. So—what do you think of the present burra-sahib?”

“Richardson? Er—well, as perhaps you know, my duties over the last couple of years have meant that I have seen very little of him. A bit weak, I think. The gup is that he leaves most decisions to Wynton. Er, that d— campaign in the mofussil went so badly, I think, precisely because he did not leave the decisions to Wynton.”

“Mm… Maybe.” Mr Lucas glanced cautiously at his driver and syce on the box of his glossy barouche and said in a lowered voice, in an execrable accent: “Vous parlez français, je crois? Dîtes à Wynton de se méfier de cet homme-là.”

One was not generally warned that one’s commanding officer was untrustworthy! “De— Du colonel?” croaked Ponsonby.

“Oui. Il n’est seulement faible,” he said in a meaning tone.

Ponsonby had to swallow hard. He had always recognised that Richardson was a weak reed—but not merely weak? “Merci mille fois, monsieur,” he croaked. “Je le lui dirai, soyez-en sûr.”

It was this warning from the well-informed Mr Lucas that set in train the sequence of events that was to lead to Colonel Richardson’s suicide and to the unmasking and subsequent disappearance of one, Felix Abdullah. And, indeed, to Jarvis Wynton’s promotion to full colonel and Gil Ponsonby’s own rise to the rank of major.

Even without the warning, however, Ponsonby had discovered a lot to admire in Mr Lucas; and he and the merchant became firm friends from that day on, finding as the years went by more and more to like and approve in each other.

—Yes, Matt, even an English colonel may be a traitor. Our Papa did not say so in so many words, but telling Ponsonby Sahib that he and Lieutenant-Colonel Wynton were to beware of Colonel Richardson was enough to warn him, you see. We do not have absolutely all the details, but we do know that some very bad men in the pay of the French paid Colonel Richardson a large sum of money for some information about what troops were being sent out from England, the which might not seem so very bad—though it was bad enough—but then the spies of a rajah who wanted the English to leave India found out about it, and this, you see, enabled them to blackmail the Colonel into letting the rajah know the position of our troops. Very many of our gallant soldiers died and had it not been for Lieutenant-Colonel Wynton’s prompt action in the field, many more would have. –Yes, Matt, it was an ambush.

Er, no, Mr Thomas, this was nigh on fifty years before the Mutiny, it could scarcely have been one of those rajahs. But very likely one of the same families, yes. –Richardson deserved to be shot as a traitor, Matt, we are all agreed on that, but that would have created an even greater scandal and brought the Army into disrepute, you see? Colonel Wynton told the man that he knew the whole, and walked out leaving him in his office with his pistol to hand. Yes, a hard man, Mr Thomas, but then, one does not survive long in the Indian Army if one is not. –Ring the bell, Antoinette, dear, the children have been so very good, and just for the once, we shall all have a taste of the sharbut goolab—the pink rosewater sherbet!

To Make a Sherbet of Rosewater

Take your Rose petals, dried as for pot-pourri or fresh if available, in the which case the pointed ends should be snipped off, or they will make it bitter. A handful is sufficient & should be soaked overnight in 2 gills [300 ml] of water. The next day take a good quantity of clean sugar, this will be as much as 1 1/2 lbs. [675 g] but much more will make it too sweet. Strain off the Roses’ water but the petals can now be discarded. Add the sugar with an extra full pint [600 ml] of fresh water & boil until it thickens. Stir in 2 tablespoonsful of rosewater essence when cooled and pour into scalded bottles as with any Cordial. Stopper well.

You want more about the spies, Matt, dearest? But we thought more about your Great-Grandpapa Lucas… No, very well, children—hush, dear ones! Very well, spies first! We shall tell you the story of Mr Felix Abdullah, who was a very bad man indeed. Perhaps you had best not repeat it to your parents, though when they were your ages, they enjoyed it as much as any. And incidentally, this will also explain the mystery which dear Antoinette queried the other day, of why Ponsonby Sahib was often called “Johnny” when he was christened Gilbert like our dear little Gil!

In India one’s native bearers are often called “Johnny” by the gentlemen: it is rather a pejorative term. When the Peninsula War was in full swing in this part of the world, Ponsonby Sahib was acting as bearer to a fat fellow in Calcutta who called himself Felix Abdullah, claimed to be part Russian, part Turkish, and spoke extremely fluent French. He lived in considerable style: indeed, held court like a nawab—a fine lord—and yet had no apparent source of income. Well, in Calcutta everyone knew everyone else’s business, so the fact that no-one knew his was in itself suspicious. It took some months, but he never suspected Ponsonby, who had darkened his skin and taken on the exact appearance of a poor half-caste servant; and he had no notion that every word he uttered to his friends in the privacy of his office was being overheard and understood, and every word of his mail read!

Eventually Ponsonby Sahib, who was very much on the alert for any mention of Richardson after Mr Lucas’s warning, picked up a reference in Abdullah’s mail to “l’officier anglais,” that is, “the English officer,” and by careful reading of all the correspondence and putting together various scattered clues, worked out that for reasons as yet undeterminable, Mr Felix Abdullah had some hold over Colonel Richardson and that it was the French who appeared to have given him this information. He investigated further, and discovered the hold was because of the payment for the information about the troops coming from England, but unfortunately he did not find out before it was too late that Abdullah in his turn had passed on the information to the rajah’s men; and so the ambush took place. He knew about it before they heard at Headquarters: a runner came from the rajah to inform Abdullah that it had been successful. –Yes, Matt, indeed Ponsonby Sahib did feel like stabbing him with a dagger then and there! Wicked man! …Oh, dear, we’ve all had too much sharbut goolab, it does tend to go to the head!

After the fuss had died down, though all the details of Ponsonby’s masquerade were not generally known, enough was, the more so as he could not get the dye off and appeared in the mess with his face black as your hat, and the officers took to referring to him as “Johnny.”

As for Mr Felix Abdullah: there were no legal grounds for accusing him. He was not a British citizen, so there was no reason why he should not correspond with French friends. Colonel Wynton advised him that Calcutta would no longer be a healthy place for him, and mentioned that he had confronted Richardson. That was enough warning: Mr Abdullah immediately elected to join a camel train that was headed up to Delhi on the Grand Trunk Road and thence the Northwest: Russia by way of Afghanistan was the plan.

No, no, that was not the end of it! You must not be thinking he escaped scot-free! Ponsonby Sahib went with him. The wicked fellow still had no idea that his simple-minded bearer was our man, of course. Ponsonby Sahib came back, in due course. Abdullah never got as far as the frontier.—Yes, Matt, you might say he executed him, if you were being nice about it.—Report gradually filtered back that his camp had been set upon by Pathans, the fierce bearded men from the northern parts. Certainly a Pathan knife was found near Abdullah’s body. The kites had been at it, but the official report said that it was likely his throat had been cut.

—Do not look like that, Antoinette: the man deserved it: he was responsible for dozens of innocent deaths. No, of course you are not sorry, Matt, and nor are we! Yes, Gil baba, the bad man died: huzza! Yes, Tessa, darling, we’re all glad the bad man died, aren’t we? Give Mr Thomas back his handkerchief, Antoinette, excessive sensibility is not attractive, and you do not see Madeleine crying, now do you? No, very like you did not suspect that Ponsonby Sahib could be that ruthless, but you never knew him in those days, when he was a young, fit and active man. It is certainly no reason for tears! –Just ring the bell, Madeleine, dear, if you would be so good: we had best all have a soothing cup of tea. Yes, Lucas & Pointer’s tea, of course, Matt! No, Gil baba, we do not stab bad men in the sitting-room! Tessa, really! Children, calm down! Oh, dear, that sherbet was a mistake, and we should never have mentioned the spies!

From the unfinished MS., circa 1899: Our India Days, Chapter 4

Today we are all going to be on our best behaviour, and if this endless rain clears, you children are to go for a nice walk, ekdum! Else you will get no story, Tessa. Very well, you may sit on your great-aunty’s lap. Yes, Antoinette is just coming, with Madeleine and Mr Thomas. We do not know why Mr Thomas did not wish to go into the Army, Matt, and it is not polite to ask. No, nor out to India like Uncle Henry.

There you all are! Flowers for three old ladies? Mr Thomas, you are too kind! How delightful! There is nothing like the delicacy of English flowers, after all, and so Tess has always maintained, though Tonie and Tiddy admire the bright colours of the Indian flowers, also. –Roses, Tessa, darling, your late Great-Aunt Josie always adored roses…

But we are not to be melancholic today, and there will no more spies or horrid things—no, Matt, it is quite decided, and we have promised your Mammas! –Yes, Gil baba, we know you would have stabbed a bad spy with a big curly knife like Grandpapa’s, but your Mamma does not wish to hear you say so, does she? –That is not amusing, Matt, and you know perfectly well what is meant!

We shall tell you a real Indian story first, and then you may stay and hear some more of our Papa’s life in Calcutta along with Antoinette and her friends, or play in the nursery, as you wish. If the nursery is boring, Matt, there are plenty of books to choose from in the library, are there not? But stay by all means, dear boy, it is your own family history, after all! Now for the Indian story. Yes, Gil, darling, they were all black as your hat, everyone in India is very dark-complexioned. But that does not mean they do not have feelings the same as us, and just like us they have children and grandchildren, too! No, this is not a story about grandchildren. This is story about a wise man, who in India is called a pundit.

Once upon a time there was a wise man, a pundit, who lived in an ordinary small house with his family and his books and his cook, who was a man, as one’s cooks are, in India. The pundit was much given to studying of his books, and of the stars, which are considered to hold great meaning in India, and the whole of his village came to him when they wished for good advice. And many in the village claimed that there was nothing he did not know. Certainly his knowledge was far, far above that of any ordinary man, for he could tell you about rajas, the quality of action, or sattva, the quality of harmony, or tamas, the quality of inertia, as well as, nay better than, any saddhoo! –That is, better than any wandering holy man, of whom one sees many in India.

One evening the pundit came into his kitchen in a terrible state and said to his cook: “Pray prepare some delightful and nourishing beverage for me, for I have sustained such a shock that I scarce know whether it be day or night!”

As it was evening the cook was naturally very perturbed by this statement and replied, rising and putting his hands together respectfully: “Master, ap mai ma-bap hai—you are my father and my mother—and if the huzzoor pleases, it is evening. But what has disturbed you so?”

The pundit sank down to a squatting position by the cook’s fire and said: “A saddhoo has just had the temerity to come to the front door.”

“Ah!” said the cook. “Begging for food, master!”

“That was my assumption, yes. I asked him what he wanted in the faint hope it would chase the fellow off, and he replied: ‘What do you have to offer?’ This took me aback and I replied crossly: ‘Do you know who I am?’”

“Indeed, honoured master,” murmured the cook respectfully, putting his hands together and bowing. “Everyone knows the master is a great pundit.”

“No, wait: at this he replied, smiling: ‘Do you know who you are?’ It was a very odd smile and I suddenly felt quite at a loss. When I had recovered my composure, lo! There was no sign of the fellow!”

The cook shook his head over it and exclaimed in dismay.

“In spite of my learning, and with all my years of study I had no ready answer to that question!” cried the pundit in distress.

The cook just looked at him blankly.

And that is the end of the story as we first heard it. But our Sushila Ayah would always add: “And since there was nothing to be said, the cook prepared a sustaining drink of rusum for the pundit, for there is nothing so good for the digestion as a hot cup of rusum taken in the evenings after the meal.”

—What, did you expect a pretty story full of rajahs and flowers and elephants? No, no, our story is very typical of the stories one hears in India! There are pretty stories, but they are mostly of gods and goddesses, and your papas and mammas have decided that they are not suitable for the baba-log. Yes, Mr Thomas, you may well say there is food for thought in it! Hindoo and Buddhist thought are, after all, two of the world’s great philosophical systems. Er—much more, if one may say so, than religions, dear sir. –Yes, Gil, darling, the pundit drank some and the cook also drank his share. No, Tessa, no-one knows where the holy man went, or if, indeed, he was there at all! Must he have been, Matt? You think about it, dearest.

The receet for the rusum, Antoinette? Every family has their own version, but we can tell you how Sushila Ayah would prepare it for us. Though mark, you will not recognise half the ingredients! There is immalee: we have never seen it here: it is a dried brown substance from a big black bean. We know that that does not sound likely, but so it is! Then, a spice that is “cumin des Indes” in French, but we have always called it jeeruh: you might have tasted it in curry powder, children, without knowing what it was. And you will not see hara dhania in England! It is a herb: the plant is used extensively from the Mediterranean all the way to the East Indies. On his travels our Papa had wonderful meals in the East Indies, where the herb is called “ketumbar” and used extensively. But we are gabbing on!

To Make a Savoury Pepperwater, In India called Rusum

Take a lump of immalee [tamarind], soak in a half-cupful of hot water, & squeeze the juice out. A teaspoonful each of black peppercorns & jeeruh [cumin] should be pounded very fine with 3 or 4 cloves of garlic. Then mix with the immalee juice, a pint of fresh water, some chopped dhania [coriander] leaves, & a teaspoonful of salt. The receet is almost done. Just fry up a little onion with mustard seed & add the mixture, simmer a little & serve hot.

Most refreshing! Er—sour and salty, dear ones, you probably would not care for it. No: no more stories of pundits and saddhoos and cooks today, and as it has stopped raining, you may run outside if you wish. No? Then everyone must sit still and quiet while we tell some of the family history. Yes, Ponsonby Sahib is in the story, Matt. No, Gil, no knives and we do not speak of those, remember? Go to your Great-Aunty Tess, darling, she has something in her pocket for you. And for Tessa, of course! –No, Matt, dearest, they are the little date squares flavoured with aniseed which you do not care for. But there will be a special treat for tea later! No, it is to be a surprise. That’s a good boy.

Now, children, your Great-Aunt Tess will read you the story, for she has long since writ it all down for us. Certainly you may have it to copy later, Antoinette, if you wish.

Henry John Lucas’s first marriage was to the only child of Mr Pointer. This produced four daughters (the older two already settled with husbands of their own when Ponsonby and he renewed acquaintance in ’08, and the younger two, Theresa and Antonia, that is, Tess and Tonie, still in the schoolroom). The second marriage, very soon after Ponsonby’s return to Calcutta, was not to the daughter of Mrs General Hayworth, as was expected by fashionable Calcutta society of that time, but to an entrancingly pretty Mademoiselle de Lafayette, come out to India in the humble position of governess to the children of a Major Bridwell. This rapidly produced two more girls: Joséphine and Angèle, known in the family as Josie and Tiddy. Their mother was a frail little thing who died in childbirth, the baby dying with her. It had been a boy; Mr Lucas never referred to this fact and tactful friends such as Gil Ponsonby never broached the subject with him.

There were women a-plenty, very many of them from very fine families indeed, who would have been happy to have settled for becoming the third Mrs Lucas; but Mr Lucas was interested in none of them, until a widowed Mrs Horton appeared on the scene. She was gentle, delicate-looking, and undoubtedly a lady: her eldest brother being a baronet who owned a fine property in Lincolnshire, her second brother a colonel of hussars back in England, the third a Collector with the East India Company, and her fourth brother that Colonel Allenby of the Indian Army who was very much liked and respected in fashionable Anglo-Indian circles. Rather naturally the widow’s exact age was not known, but she appeared considerably younger than Mr Lucas; the which did not stop them marrying. Nor did the fact that the pleasant Colonel Allenby felt constrained to murmur in his sister’s ear that Lucas, though a decent fellow, was scarcely one of us.

Mr Lucas and the third Mrs Lucas had many happy years together, his four younger daughters all adoring her and she them, but sadly produced no children of their own. The which, unkind Calcutta tongues said, proved the woman must be mutton dressed as lamb!

It was about five years after he decided to remove his family to England that Mr Lucas died. He left no male issue. His will made generous provision for the third Mrs Lucas during her lifetime, and provided large portions for each of the older married daughters, even though they had received very generous settlements upon their marriages. However, the four younger girls, Tess, Tonie, Josie and Tiddy, received nothing outright. Reasonable amounts were to come to them upon their marriages to men of whom their guardian should approve, or, failing marriage, at the age of thirty-five. But all the rest of Henry Lucas’s enormous estate, comprising his entire interest in the thriving import-export business of Lucas & Pointer, all the ships belonging to the Lucas Line, the very new tea plantations up in the hills near Darjeeling, huge acreages of warehouses in Calcutta and London, the white house in Calcutta, various commercial properties in Bristol, London, and Southampton, a splendid London house in fashionable Blefford Square, and a large country estate in Kent, near the coast, together with the guardianship of the said daughters, was left to Gilbert Allan Joseph Ponsonby.

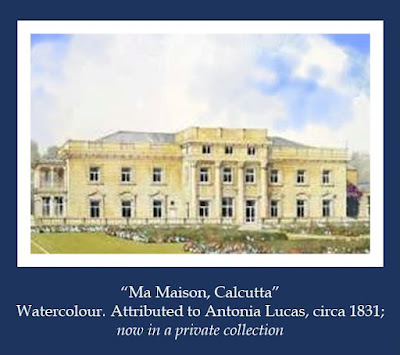

The house in Calcutta called “Ma Maison” and one third of the remainder of the estate were to be Ponsonby’s outright. The other two-thirds were to be held in trust, the substantial income coming to the four youngest Lucas daughters: but upon the condition that one of them marry the said Gilbert Allan Joseph Ponsonby within five years of their father’s death. Should he not be already married at that time, in the which case only a quarter share of their two-thirds was to come to the girls upon their marrying men of whom he should approve, the rest of the income remaining in trust with the capital.

—There now, that has explained it all very clearly, odd though of course Papa’s will seemed. Not explained it enough, Antoinette? Alas, there is no more to say. You would wish to know how Ponsonby Sahib felt about it, Madeleine? No, pray do not hush her, Mr Thomas, it is a natural sentiment! You want to know, too, Matt? And you, Antoinette! Goodness, that would seem to be what the political gentlemen call a quorum! Well, dear ones, you must realise that at the time none of us knew Ponsonby Sahib well at all—we were here in England, remember. Er—yes, Tiddy is correct, perhaps Ponsonby’s letters to Colonel Wynton—Lord Sleyven, one should say—might clarify the picture, but— Pray do not cry out, Matt! Tiddy will read out the appropriate portions of the letters for us, then. Thank you, Mr Thomas, if you would be so good: they are in the library—all of his letters came back to him after Sleyven’s death, you see. Matt will show you—thank you, Matt, dear boy. Your Great-Aunt Tiddy will E,D,I,T for the baba-log, Antoinette, never fear!

Extract (1). Letter dated “Calcutta, 4 March 1827”

... You may well say, many men would leap at the chance of such a fortune. I don’t think it’s to flatter myself to say that Henry Lucas knew I am not one of them. Then—why me? Given our friendship it was not unreasonable that the man should leave his daughters to my guardianship, but why the other? Did he perhaps not really expect that the girls and their fortune would end in my care, but would all be safely married off by the time he had to leave them? Well, I am thinking it over, Jarvis; I shall not make any precipitate decision.

In the meantime, things seem to be going from bad to worse, here: Col. Moriarty has managed to set the regiment by the ears. His is one of those ineffectual, petulant characters which is not ameliorated by command, alas. He don’t see the need for any sort of investigatory, not to say undercover rôle, regardless of the fact that I have been performing it for over twenty years with reasonably satisfactory results, and has told me to my face that the office will be closed down and myself expected to cut my hair and turn up at the mess decently dressed. In so many words: a sense of humour is but one of the attributes the man lacks. I am doing my best to work with the fellow, without much success. Dare say half of Calcutta assumes my nose is out of joint because I did not get the promotion to full colonel myself, but as you know, I have no desire whatsoever to command a large body of men. Hitherto I had not seriously thought of selling out, but this d— inheritance makes it possible, don’t it? Well—as I say, I shall not rush into anything.

***

Extract (2). From an undated letter from Calcutta, early April 1827?

... I have to admit, my first impulse was simply to wash my hands of the whole thing. The four unmarried Lucas girls are not alone: they have their adored stepmamma, and Mrs Lucas has her own family to give her aid and support. I suppose I could remain their guardian in name only until they reach their majority: it seems the simplest solution. As to the inheritance—in my innocence I felt it might surely be possible to refuse it, let Henry’s daughters have the lot, so I took advice from a respectable firm of Calcutta solicitors. Dare say you can envisage the scene, Jarvis: the unspoken advice was, only a madman would not leap at such a fortune. And the spoken was what I had feared, alas: it is impossible to break the will, and my refusing the bequest would result not in the larger part of the fortune’s reverting to the Lucas girls, but in its being administered in trust, eventually, after the death of the last of them, being divided equally amongst their heirs. Not an entirely cheerful prospect.

So I cannot reasonably give the thing up. I admit I am tempted neither by the thought of a fortune, nor by the thought of England. But it does seem highly unfair that Theresa, Antonia, Joséphine and the funny little one, Tiddy, should see scarcely a penny of their father’s fortune. And then, India is becoming less and less attractive, with d— Moriarty in your shoes.

After seeing the lawyers I mulled it over for another week, and then got round to the house. For some years it has been used only when Lucas visited the Calcutta office, but the grounds are still looking as impeccable as ever—the which is due entirely to the vigilant staff of Lucas & Pointer, and not, as I am sure you will readily grasp, to any devotion on the part of Lucas’s Indian servants! No, well, there is no point in putting the effort into maintaining the grounds if the burra-sahib ain’t there, is there? Logical, in its way.

I think you will appreciate what followed, dear man, so I shall tell it in some detail. There was no-one on duty in the little thatched shelter by the gates, of course, but they were not locked, so I opened them with my crop as I had been used to in Lucas’s day. I reached the sweep, and was about to turn to the right in the old fashion, when the front door burst open and a stream of babbling, sobbing persons poured out and prostrated themselves at my feet. Or rather, since I had not dismounted, at my horse’s. It was not clear whether they were weeping because Lucas Sahib was dead—a quite genuine grief, not in the least quarrelling with the inclination to neglect the upkeep of his grounds—or because Ponsonby Sahib had come at last, unquote. I did not enquire how the D— they knew the details of my inheritance: any answer would merely have been what they thought appropriate for me to hear. Doubtless a Moriarty would condemn them for that, along with the rest.

I was urged to come inside, and after the clutching at the legs, the touching of the foreheads to the feet and so forth was over, managed to do so. The big house was cool and dim: a little dusty, but not too bad. Old Ranjit Singh showed me into the library, and asked respectfully when they might expect the sahib’s baggage. To which I replied: “I have not yet made up my mind to move in.”

Ranjit bowed deeply and produced: “Naturally it will be taking time for the sahib to sell out.” I can’t say this surprised me, but I had to wince.

His next effort was—I shall not spare your blushes, Jarvis—“Ah, Colonel Moriarty is not being half the man that Colonel Wynton Sahib was,” with a deep sigh. To which I returned merely: “Is the house habitable?”

The house would be ready ekdum—&c. Be that as it might, certainly the kitchen was active, because trays and trays of refreshment began to be brought in. Conveyed, naturally, by streams and streams of servants. As I ain’t a Moriarty I ignored the fact that I was not hungry and sampled a little of the food and drank several cups of tea. After a while a couple of hovering forms appeared outside the French windows, and the bhai, Ram, salaaming profoundly, kindly offered to chase “those budmushes” away. The which offer I refused.

I went and drew the muslin curtains back from the opened windows. As I had thought: mali and the head groom. Behind them might be glimpsed mali’s three nephews, four assorted syces, all related to the head groom, naturally, though I cannot not recall precisely how, and, over by the far end of the trellis, an occasional flicker of a bright saree or kurta, signalling the presence of the females of the families. I spoke kindly to mali and the head groom and they both prostrated themselves.

From behind me Ram’s voice noted disapprovingly, not to say predictably: “Those budmushes must not come onto good carpets, sahib.”

At this I replied: “I am sure they don’t wish to,” in the language of his home village. I refrained from looking, but could feel him dropping to his knees and prostrating himself behind me. “Yes, good,” I agreed, as the head syce tried to tell me there were excellent horses in the stables. I was aware of some flurry over by the trellis. Then a little brown child in a grimy white dhotee and a tiny silk jacket was pushed forward by several thin, brown arms jingling with bangles. He staggered up to the verandah, clutching a small bunch of flowers. After a certain amount of prompting had taken place he allowed me to take these from him.

I thanked them all formally—just to make sure they got the point, repeating it in two languages. Then I firmly closed the French doors. Before I could turn round Ranjit Singh’s voice noted approvingly from behind me: “That is the only way to dealing with these outdoor-wallahs, sahib.”

Lor’, would I be reduced to speaking the major-domo in the language of his home village? “Ranjit,” I said clearly in English, “I have not yet made up my mind whether to accept Mr Lucas’s bequest and come and live in his house. Perhaps you would see that those of the other servants who need to know that, are told? In the meantime, please carry on just as you have been doing.” With that I firmly headed for the front door—perforce clutching my bunch of flowers.

My bony nag had been watered and was munching from a nosebag. Round its neck hung a scraggy string of marigolds that had certainly not been there when I arrived. Just coincidentally a much glossier horse was also on the sweep, snorting at the bit, prancing and tossing its fine head. Somewhat fortunately I remembered the name of the man holding—make that ostensibly holding—its head and was able to order: “Manu, stop irritating that horse and take it back to the stables.” Much abashed, but not neglecting to assure me that I was his father and his mother—ap mai ma-bap hai—the syce led the glossy creature away, and I mounted my bony nag. Over on the wide lawn, mali was now visible watering busily, a pointless exercise, of course, in the middle of the day. Further down the drive one of his assistants was raking gravel. Nearer the gate another was digging out weeds from the verge.

I rode slowly down the mandal, completely ignoring this spectacle. At its foot a sweating person in a white uniform jacket, buttoned crooked, threw a smart salute. I allowed him to open the gates, then paused. “I noticed the nameplate has been removed from the gatepost,” I said in the local dialect. “Why was that done, do you know?”

The man bowed until the tip of his nose touched his bony bare knees. “The sahib from the offices of the burra-sahib ordered it done, huzzoor.”

To which I incautiously returned: “I see. I’ll contact the offices, then.”

Avoiding my eye, the gatekeeper explained meekly: “The sahib said, begging the huzzoor’s pardon, great zemindar, huzzoor, that it was not funny.”

No, well! As you may recall, it was shortly after he married Mlle de Lafayette that Lucas named his house “Ma Maison”. I was up the country at the time. When I got back I noted that it lacked but the L, and why did he not go the whole hog and call it Versailles? He had been preserving his countenance wonderfully, but at this he broke down in sniggers, awarded me a buffet on the shoulder and admitted that no-one else in the whole of Calcutta had dared to say that to him! A small moment, perhaps, but the sort that goes a considerable way towards cementing a friendship.

To the gatekeeper I said only: “I think it is funny, and Lucas Sahib always thought it was funny. I will arrange to have it put back.” Naturally eliciting the response: “Yes, indeed, great zemindar, huzzoor, it is funny: very funny!”

Of course the man cannot read in any language. “Indeed,” I agreed. “And please do not call me ‘great landowner.’” –Do not tell me it was wasted breath, Jarvis! “No, indeed, oh defender of the poor, huzzoor,” he bowed. “A thousand pardons, huzzoor.”

I let it go at that, gave him a coin, and rode out into the warm, dusty streets of the city.

***

Extract (3). From a letter from Calcutta, dated “April 1827”

... As I think you know, Dr Little is no longer in active practice: he has retired to a pretty little house on the outskirts of the city. I had not seen him for some time, the which did not wholly explain why he sent a chitty announcing he would dine with me in the mess. On the appointed day he came in looking cautious, so I was enabled to say as we shook hands: “Calm down, Doctor: it ain’t either a Saturday or a Wednesday.”—Moriarty has appointed those as the days he dines in the mess.—“Never know, dear boy,” he said. “The sky might have fallen, or the world ceased turning in its orbit, without my noticing. How are you?” On my replying innocently that I was very well, as ever, he sat down, noting blandly: “Richer than you was ever, though, Gil, so they say. I’ll have a chota peg, thanks.”

Presumably it is all over the city. I pointed out somewhat heavily that I have not yet accepted the bequest, at which Little raised an eyebrow and murmured that he had heard there were strings attached. To which I snapped: “Never tell me the precise nature of the strings is not all over Calcutta, too!” Blandly he returned, accepting a glass from the bhai, that there were several versions, but no indication which, if any, might be the correct one.

Over the chota peg he opined that if Henry Lucas wished for the thing, it’ll be in my best interest to accept it, remaining unaffected by my sour reception of his sage words. So I revealed flatly that Lucas has left me the house, plus a third of the rest of it, and the four younger girls get the income from the rest, provided I marry one of them. This appeared to be specific enough for him: at any rate he looked distinctly numb, the which I do not think was entirely due to the quality of the mess whisky. –Moriarty’s latest, believe me or believe me not, is to inspect the mess bills—that is, the bills for what is purchased and the chaps’ bills! Gone down about as well as you might expect.

After some time the doctor managed to croak that it did not sound like Lucas and to ask how many of the girls are still unmarried. To which I was able to reply: “All four younger ones.” Well, you know Little, he don’t mince words. “I wouldn’t take the second gal: Tonie, was it? Always a bit of a nag, weren’t she? Managing gal, too. Don’t think you’d like that, old man. Dare say Miss Lucas would suit. Conformable sort of gal, weren’t she? What’d she be, twenty-five or so, now? Didn’t Lucas buy a dashed great mansion in Kent? Let her play the lady of the manor to her heart’s content. You wouldn’t need to see much of her.” I thanked him for that kind advice, and after enquiring what I had expected, he produced: “What about the pretty one? About fourteen when they left. Well grown for her age.” –With a wink. At the which I was forced to remind him that Josie must be about nineteen now, and I am forty-seven. “Are you, Gil? Time do fly, don’t it? Dare say she wouldn’t say no, if the fortune came along with it,” he said with another d— wink.

“And I, of course, would wish for a wife on those terms,” I said arctically.

So he asked me, kindly enough, whether they got anything if I got upon my high horse and whistled a fortune down the wind? (More or less, in the intervals of bellowing “Bhai!” and having his glass recharged.) At which I told him what I wrote you, ending: “They get a very much reduced amount unless one of them marries me. Most young women would find such an income more than sufficient to live on very comfortably for the rest of their lives.” Little scratched his chin and suggested that maybe that is what Lucas wanted for his girls. I told him that I did consider that, but Henry Lucas was the most clear-headed man I ever met. He of all people must have realised that that could result only in resentment and discontent. He would not have wanted his girls to end up as four embittered, discontented woman.

The good doctor then suggested it might be a test of character, to which I responded acidly: “Of mine or theirs?” He was so kind as to tell me Lucas would not have had to test mine. At which point dinner was mercifully announced. He ain’t all bad, as you know, and chatted cheerfully on indifferent topics during dinner, and for a while over drinks. Then he suggested I ride home with him, so I got into a tonga with him and spared him the pains of broaching the subject by telling him to go on.

He did not approach the topic in the way I had assumed he would. He scratched his chin slowly and said: “Knew Lucas had had rheumatic fever, did you?” I was somewhat taken aback and confessed I did not, asking when it had been. “Couple of years after he first came out. Just a lad: he was stout enough, only reason he came through it, in this climate. It weakens the heart,” he said unemphatically. “He had one heart seizure about three years after he married the third Mrs L. The regiment wasn’t here, no way you could have known. The last time that I know of was during his last trip back here. You was up the country—last mission before Moriarty pulled the mat out from under your feet, wasn’t it? Told him it was a warning and he’d have to take it easy. Dare say he ignored me. Didn’t know how to take it easy, never mind he claimed to be living a retired life in England. I didn’t mince words with him, Gil. He knew he might go at any time. The will must have been intended to make sure the daughters were safe if he was took off sudden.”

I was very shaken at the implications of this—as you know, my assumption was that he had not expected to die until the girls were safely married—and did not speak.

The d— man then coughed and suggested: “My place or yours?”

I was frankly flabbergasted, Jarvis. Now that Moriarty has made me cut my hair and pulled me off investigative duties I’m officially quartered in the chummery with the younger officers, and I’ve always been d— careful about the thing, as you know. “What?” I said feebly. Little was completely unmoved, informing me blandly that if we went back to his house, his bhais would be just about capable of serving us up a watery chota peg or a cup of chocolate with lumps in it and that he had not had a decent cup of chocolate in all the years since his wife died, and that if he asked for pukkorahs his blasted cook would make his life Hell for the next two weeks, because the minute he left the house he’d have let the fire go out, whereas at my house we could undoubtedly get a decent little hot supper with some home-made pickles!

I am quite sure you can guess what came next, Jarvis: I asked him who told him, assuming it was Lucas, and he admitted it was you, before you left India, just in case I went off on one of my missions and never came back. Adding kindly: “Wynton were like that, hey? Dashed careful officer. Excellent colonel.”

I could not but agree, and Lord knows I am not blaming you, Jarvis: Little, in spite of his manner, knows how to hold his counsel, but in the event, it was a wasted precaution on your part, was it not? I said something to that effect and something bitter about Moriarty, and he said: “Aye, well, in your shoes, I’d be grabbing the chance to sell out. Moriarty’s an ineffectual ninny. And a bully, from what I hear. –Want to give the syce the direction?”

Resignedly I gave the driver the direction and we jogged on home. It must by this time have dawned on Little that the scheme proposed by Lucas’s will is impossible, as I am married already. And though the English sakht burra mems of fashionable Calcutta know nothing of it, Lucas knew the whole story, so if he was aware he might be took off at any moment, why the d— will?

The Facts of G. Ponsonby’s Indian marriage as I know them.

Indira was the child of a wealthy Indian merchant who had made a marriage for her with a spoilt young man whom Ponsonby had been obliged, for reasons which had nothing at all to do with the fellow’s wife, to remove permanently from the scene about a month after his wedding. The man’s family kept the substantial dowry and returned the little widowed bride to her father. Whether it was because the merchant had twelve other daughters to marry off or not, was never ascertained: but certainly Ponsonby, who was at that time, in order to facilitate his undercover activities, living in a shabby bungalow rather then the chummery, woke up one morning to find a sobbing little bundle on his doorstep. His responsibility, it appeared. I know many men who would have shrugged, and kicked her aside; others who would have taken her in for as long as she pleased them, but none who would have married her. He did so, but at my and Henry Lucas’s urging never revealed the marriage to our compatriots: it would have damned him utterly in the eyes of Calcutta society. He did not particularly care for Calcutta society but he took our point that it would be a waste of a good man should he be asked to resign his commission over the thing.

A neat little bungalow on the outskirts of the town in a largely chee-chee area where the marriage was more likely to be accepted was found, and Ponsonby installed Indira there with a parcel of servants, the which gradually augmented itself, as one’s Indian household is wont to do, mali proving to have not only a wife and eight children but also a brother who assisted with the scrubby lawn and scattered flowering shrubs, the syce, a widower, having his brother’s widow and her six children to keep—&c.

I do not claim he is a saint: he did not refrain from marital relations with the little creature whom he had married out of pity. She was certainly pretty enough, and as she was his, why not? There was, too, the additional factor that she would not have understood had he exercised some sort of gentlemanly restraint and would in fact have become a scorn and a hissing amongst their chee-chee neighbours of the little casteless community where their house was situate. In due course the union produced a little round-faced boy and two thin, brown little girls. Sadly, the boy was carried off in one of the epidemics that regularly sweep the sub-continent. At the time of writing, however, the wife and little girls are still alive.

—Jarvis Wynton. In cantonments, 1821.

No, well, such things used to happen out in India, dear ones, and there is no reason in the world for those faces. Yes, Gil darling, Ponsonby Sahib did once have a little boy, but his name was not Gil like yours, but Raju, which means “little prince,” is that not pretty? Yes, Tessa, Raju was the little boy for whom the pictures of the animals were drawn. Those are their Indian names underneath them in the funny writing. No, dearest, he was too little to be able to read. –Matt, dear, little Indira was not as black as your hat, but a nice brown colour and very pretty. She would have died had Ponsonby Sahib turned her from his door. Her own family had thrown her out, you see. Widows are treated very, very badly in India, dear boy, and this poor little widow was not even as old as Antoinette and Madeleine. About your cousin Margaret’s age, dear boy. Indian girls are married off very young. Yes, Antoinette, dearest, that is quite right, we must make allowances! Now, shall we continue? Or you little ones might run and play— No, very well, stay if you wish.

Extract (4). From a subsequent letter dated “30 April 1827”

… I have not confided the story of the will to Indira: I rather think that any hint of my going home to England would result in a storm of hysterics. And in any case, I have long since discovered that we cannot not really talk: for we have nothing in common save our children and our mutual membership of the human race. It is not her fault that she can share none of my interests: she received no formal education whatsoever and knows nothing of the wider world. She learnt a good deal about cooking and keeping household from her mother, and having been semi-adopted by the woman from next-door, a substantial chee-chee matron who happily took up the rôle that is normally that of a young Indian wife’s mother-in-law, has learned a good deal more during the years of our marriage, together with quite a lot of lore about salves, potions and medicaments: quite often we discuss receets. As you know, I am very interested in Indian music, but Indira never learnt to play an instrument and can sing only a few little ditties which she doubtless absorbed at her mother’s knee. I would have found her teachers had she shown the slightest aptitude or inclination, but she has none. And she cannot read, like all girls of her class, and does not wish to learn. In the early days of our marriage I tried reading poetry to her, but found she quickly become bored.

I hasten to stress, dear man, that I have by no means been unhappy in the relationship, perhaps because I was old enough when I married her not to expect any more of her than she was capable of giving. I have never been in love with her, but I am very fond of her, and whatever certain of my colleagues might do in my position, have no intention of abandoning her, unexpected fortune or no. And then, do most Englishmen of our class have anything approaching marriages of true minds? Not according to my observation—no. Yourself excepted, of course!

I think I had got as far, in my last, as telling you that Little had demanded to come home for hot chai and pickles. Indira had probably been asleep: if I am not in for dinner she normally goes to bed with the birds. Nevertheless she very quickly appeared, saree well pulled over her face, greeting us with a series of low bows, and offered food. Little settled back apparently quite at his ease on one of our low, Indian-style couches, happily allowing her to serve him hot pukkorahs and a selection of pickles, and I to pour him, not a cup of hot chai, astoundingly enough, but a chota peg.

Cauliflower Pukkorahs

Ingredients: 1 small or 1/2 large cauliflower, cut into flowerets, 1 1/2 cups besan flour, 1/2 to 3/4 cup water, 1 teaspoonful cumin powder, 1 tablespoonful coriander powder, pinch of cayenne, pinch of hing (asafoetida), 1/2 teaspoonful turmerick, 1 teaspoonful Indian spice mix, 1 teaspoonful salt, ghee for deep frying.

Mode: In bowl combine flour and spices. Add water till it becomes a medium-thick pancake batter. Heat ghee until hot, testing with a drop of batter. Dip cauliflower pieces in batter & put in hot ghee a few at a time. Fry until golden brown.

Sufficient for 4-6 persons as a snack or 6-8 as part of a meal.

(From Great-Aunt Antoinette. Copied by J.W.)

As Indira retired to the kitchen regions the good doctor noted calmly: “I’d pay a fat chee-chee a decent sum to take her off me hands, if I were you.” Oddly enough, as I told him, that is what the very respectable firm of solicitors which I consulted advised. I pointed out to him, as I did to them, that we are married. Little, at his most irritating, merely chose a cauliflower pukkorah and dipped it in a beetroot and date chutney, remarking approvingly upon the latter and mentioning that he thought he had eaten something similar at Lucas’s place. I admitted heavily that I had had the receet off him.

He then added on an uncomfortable note: “Uh—look, old man, if it weren’t a Christian ceremony it don’t count.”

To which I returned sweetly: “With whom, Doctor? Your God? Hers? The Lucas girls? The Archbishop of Canterbury?”

You know Little: not much throws him, and he replied with some feeling: “Well, the Archbishop of Canterbury, for a start! Might as well be realistic about it. Know a round dozen chaps what’ve gone through a ceremony of marriage out here, then gone back Home—” At this point the expression on my face apparently registered. “No, very well,” he said glumly. “But the thing is, old boy—well, several points. But can you envisage taking her back Home?”

Of course I said I could not: she would hate it. It is completely outside the scope of her experience: nothing could prepare her for it. I do not think that was precisely what the doctor had meant, but he nodded and asked me—at last—what the will said if I was married already. As I wrote you earlier, it still lands me with the guardianship of the four younger girls and the trusteeship, with a third of Lucas’s estate and Ma Maison outright, but the girls get only a quarter of what they would get if I were free to marry one of them. Little thought this seemed unfair, to which I could only reply: “Yes, don’t it?”

After further thought he produced: “Look, Gil, seems to me the fairest thing for them girls would be to take up the guardianship. But thing is, if you go and admit you’ve married an Indian woman—or if it gets out—you won’t be able to give the girls any sort of decent life out here, because the whole place’ll cut you. And enjoy doing it. There’s still a good many noses out of joint because Lucas married that little Frenchwoman in the teeth of Mrs General Hayworth, and then ignored all the cats and their daughters after she died, and took Colonel Allenby’s sister in the end.”

I replied somewhat dazedly: “Are you implying they resent his snubbing their daughters in favour of Colonel Allenby’s sister or that they resent the fact that a mere merchant was able to nab a colonel’s sister?”

“Both, y’fool,” he said with a sigh. “The sakht burra mems are like that, in the case you hadn’t noticed it while you was off jaunting all over the mofussil shooting spies. So—England, then?”

This was no more than I had expected, but I pointed out that I cannot just abandon Indira and the two little girls. He thought I might leave her with a brother, making sure there was a decent sum set aside for her welfare, out of course. “You’d trust this putative brother, not to mention his putative wife, not to grab the decent sum for themselves and turn the poor little soul into some sort of household slave, would you?” I asked sourly, reminding him that abandoned wives are not treated kindly in India—and they would most certainly see it as an abandonment. At which the d— man informed me that my trouble is that I have a conscience.

He then coughed and produced from his pocketbook a letter addressed to me in the very clear hand of Henry John Lucas!

“How long have you had this?” I choked.

A year or so, was the answer. Henry had told him not to give it me unless he died before the girls were married, and also told him to say it wasn’t a codicil. I opened it forthwith—Little meanwhile helping himself to another whisky. Unfortunately it proved unilluminating. I copy it here verbatim for you, Jarvis, and if you can make anything at all of it, I shall be very, very glad to have your opinion.

*

My dear Gil,

If you’re reading this, it should be because I’m dead, two or more of my girls are still unmarried, and your Indira is still above ground. If not, I presume Little is dead, in the which case you may stop reading.

I dare say by now you think I’ve run mad. The thing is, taking the girls home to England has not turned out as well as I had hoped. It did stop Tiddy from running off to the bazaar dressed like a boy, but that is about all that can be said for it. It has done naught for the other three except turn them into a set of simpering, selfish English Misses with not a thought in their heads but beaux and gowns. And I didn’t work all my life in order to leave a fortune to a set of English Misses what wouldn’t give a decent working fellow the time of day.

This is not a codicil. It is just to tell you that the will means what it says. You must decide for yourself what is best for the girls. My wife’s Allenby connections are offering them all a Season in London. What that means is, spending my money on hiring a house and giving extravagant parties while they make d— sure their imbecile of a son offers for one of my lasses.

I’ve left you Ma Maison. You, Mrs Lucas and Tiddy were the only ones that cared for it, outside of me and old Pointer, God rest his soul. It’s up to you whether you live in it or not.

The girls do not know it, but Mrs Lucas is not well. If she outlives me, I do not anticipate it will be by much. Pray do not leave Tiddy with the Allenbys if you can help it, my dear Gil. She cannot stand Sir James or his wife.

For the rest, I cannot advise you what would be for the best, because, as I say, my decision did not turn out well. Do as you think fit.

Ever your loving friend,

Henry John Lucas.

*

I passed it to Little to read, but he could only conclude: “Dumped it all in your lap, hey?”

How true.

Kindly he then said that he would be happy to talk it all over at any time I felt like it. I thanked him and acknowledged that he is possibly right, and the best course will be to allow all of the dashed nobs, either here or in England, to believe that the girls are simply left to my guardianship. When the fortune-hunters start offering for them, will be time enough to reveal the true facts.

Grinning, the doctor agreed: “Aye. What was it, a quarter of what they could expect? Maybe Lucas had that in mind all along, Gil!”

Perhaps he did. The d— will is, in fact, as I said to Little, at the same time a test of my character—Little was wrong about that—of Henry’s daughters’ characters, and of those of their suitors.

Having reread Henry’s letter several times I am inclined to think it hints that as his England venture was a mistake I should think about bringing the Lucas girls back to India, to Ma Maison. But am I merely imagining it because that is my own inclination? Well, in any case I am free to use my judgement. Perhaps it will be best to see for myself exactly how things are, in England, before I make any decision about where the girls should live.

It occurs to me that perhaps Little would keep an eye on Indira if I go back to England? I shall ask him: at least that will be one worry off my mind.

From the unfinished MS., circa 1899: Our India Days, Chapter 4

It took some time after that, but eventually Ponsonby Sahib made up his mind to it, and resigned his commission. And, since the obliging Dr Little readily agreed to keep an eye on Indira and their little household, Ponsonby Sahib, having visited Ma Maison again to assure Ranjit Singh that although he was off to England to see Lucas Sahib’s daughters he would be back, and would wish to live in the house, went home to England.

—Well! You younger ones have been very, very good, listening to our long story! Hush, Matt, dear, never mind that little Gil, er, N,O,D,D,E,D O,F,F, he has been so quiet and good. Yes, you, Gil baba, what a good boy!—The full version of the correspondence may go in your notes if you wish, Antoinette, dear, certainly.—Thank you, Mr Thomas, we’re very glad that you agree with us that Ponsonby Sahib acted entirely honourably.

Quite correct, Matt, that was Great-Grandpapa’s house in Calcutta, Ma Maison, where your Uncle Henry now lives. Is it time for tea? Oh, good! –You liked hearing about the big house and Ponsonby Sahib and his horse, Tessa, dearest one? Yes, so did we all! Yes, darling: Ponsonby Sahib came home to England! Did he go away again? Well, that remains to be seen! –Yes, please do ring the bell for tea, Mr Thomas, if you would. In due course, Matt, dear, you will see how it came about that Uncle Henry is living in Ma Maison. No, no, dear boy, too many questions! We shall tell it all, but not all at once!

... Ah! Here is the surprise! The sujee biscuits that are Matt’s absolute favourite! Do try one, Mr Thomas, we promise you they are not as odd as they sound! –Hush, Tessa, there are plenty of other things here. –Yes, cakey for Gil baba, too! –Good gracious, Antoinette, still writing? The receet for the sujee biscuits? Very well, dearest, one last receet, but then you must eat something!

This is a receet of Nandinee Ayah’s, and, though we would not have dared to say so, we much preferred it to Sushila Ayah’s sujee balls!

To Make Semolina Spice Biscuits

Take 4 large spoonsful of ghee—that is, butter—and 4 of sugar, beating them together until creamy. Add a cup of sujee (semolina) & the seeds of half a doz. elaychee [cardamom] pods ground, and beat well. Leave in a warm place for half an hour. Then knead well, and shape into small flat cakes. They may be decorated with chopped nuts. Bake till golden.

Elaychee is an Indian spice. Cinnamon might be used.

Next chapter:

https://tamasha-aregencynovel.blogspot.com/2024/03/ponsonby-comes-home.html

No comments:

Post a Comment