20

“The Search Is Finished”

... Well, there you have it, Jarvis. My poor little Indira is gone. We gave her the Hindoo funeral pyre: the children would not have understood anything else.

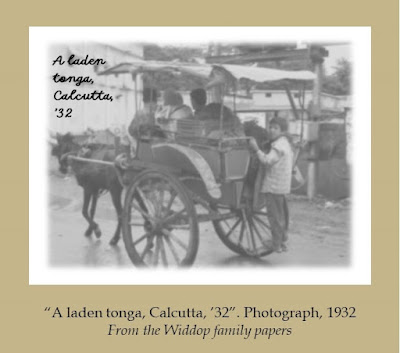

There is much else to tell you, but I confess I am at a loss as to how to put it. Well, let me say straight away that Welling has proven himself to be a thoroughly decent fellow, and has accepted my little daughters with great kindliness, privily offering to knock any fellow down who dares to breathe a word against them! Robert Voight also has been thoroughly decent throughout. –I am jumping ahead of myself: I’m sorry. Well, you know Paul Voight, his brother, of course. Commander V. is just such an upright, honourable fellow, though something of a ladies’ man. Well—good-looking fellow, widower, several fat prize ships to his credit, we gather—result, pursued by all the hags of Anglo-India. As to how he became mixed up in this— No, well, coincidence, really, Jarvis. In Calcutta at a loose end, avoiding Patapore because his sister-in-law has a particularly lush widow with the reputation to match lined up as the next Mrs Cmmdr. V., called at Ma Maison at the very time that Little had rushed round to fetch me to Indira’s bedside. He very kindly offered to take the message to me at the office, as Little wished to get back to Indira without delay. As—typical Little—the message was baldly that Indira was dying and I was to get over there, he was aware that something was up. Into the bargain aware that she was my wife! Not absolutely sure that it was the good doctor who imparted that fact, might have been d— Ranjit Singh. Sorry, I’m becoming incoherent again. Turns out Ranjit has known all about Indira for years—I think, ever since I married her, pretty much. How, do not ask me! Well, that is India, is it not? No such thing as a secret.

No, that is not all. I had best come straight out with it, Jarvis. I told you about little disfigured Miss Morgan, did I not? The one who had been looking after Indira and who rushed round with the message that Josie had got into Hatton’s carriage. Yes. Well, the reason that she recognised Josie and was, on looking back, so upset about it, was that she was never Miss Morgan at all, it was d— Tiddy!

If you need to recover your breath, old man, you are not the only one. I had best tell you exactly what happened.

Voight gave me his message, let me take his tonga, and I rushed straight home to Indira and the girls. The supposed Miss Morgan was sitting with them, draped in one of her hideous English outfits. I barely had time to say: “How is she, Miss Morgan?” before George Little burst in, panting. He checked Indira—very, very weak, scarce breathing, poor little angel—and then to my astonishment said to Miss Morgan: “All right, get into the other room and stay there. I’ve spoken to Ranjit Singh.” She went, saying nothing, and I of course stared at Little, thinking he had lost it.

“Don’t ask, Gil,” he said, patting my shoulder. “Tell you later. Let’s just wait, mm?”

So we waited, and my poor little angel just drifted away from us. None of us could have said precisely when she went: her breath was so very faint at the last.

The girls were very upset, of course. They wanted to stay with her, and Little, saying we had best leave them to it, more or less pushed me bodily into the sitting-room. “Look, Gil, this is going to come as a shock,” he said grimly. “You had best sit down.”

I sat down, looking from him to the silent, huddled figure of Miss M. in some astonishment.

“Go on, tell him, or I will,” he said to her.

For answer she simply removed the appalling giant black hat with the impenetrable black veil and lo! It was Tiddy. “A shock” does not even begin to describe my feelings, Jarvis!

“One cannot deny,” said George Little grimly, “that she has been very kind to Indira and the girls. You may well ask, why do it in a d— disguise, though.”

I nodded dumbly.

“Because no-one was supposed to know you were married, of course,” said Tiddy, attempting to look defiant.

“Tiddy,” I croaked, “how long have you known?”

“Well, always. I’m not very good at dates. I suppose I was about four. I was under the library table. You and Papa were talking about it.”

“That would have been in about ’14, Gil: she was born in 1810, I remember that: middle of the rains, appalling night, the roads were a foot deep in mud, thought I’d never make it to the house,” noted the doctor.

I was quite numb. I agreed that 1814 was the year I married Indira, and, it then dawning that Tiddy must have known when I turned up at Tamasha, asked why on earth she hadn’t spoken up then? She stuck her chin out, replying: “You didn’t say: ‘I cannot marry any of you because I’m married already,’ so I didn’t say anything, either.”

The doctor coughed suddenly. “Few faults on both sides, Gil.”

I agreed limply. And asked weakly: “But why the disguise, Tiddy?”

“Well, in the first place I thought Indira would not accept an English mem.”

I had to admit that was probably so, though pointing out that Tiddy might be English and female but she scarcely falls into the category of the sakht burra mems of Calcutta society.

“Nevertheless. And in the second place I thought that as you obviously didn’t want us to know about it, I had best not turn up as me.”

“Mm. Uh—why did you turn up at all?”

She stared at me. “To look after her, of course, Ponsonby Sahib, because she was sick!”

At this, Jarvis, as you may imagine, I barely refrained from shouting at her. But managed to ask: “Tiddy, how did you even know she was sick?”

“Mrs Ashby came round and spoke to Ranjit one day—at the back door. She didn’t know how else to get hold of you.”

“Ranjit, one collects, knows everything and has always known,” put in Little drily.

“Yes, of course,” Tiddy agreed.

I passed my hand over my face. “So that note which, as I thought, Mrs Ashby left—”

“I wrote it. She can’t write very well.”

Jarvis, at this point I could frankly have wrung her neck for her! Took a very deep breath and said, keeping a tight rein on my temper: “Tiddy Lucas, are you implying that Mrs Ashby has known all along who you are?”

“Yes; she’s not stupid,” she replied calmly.

At this point the good doctor noted calmly that Lucas would have given her a d— good beating, and I could not forbear to agree, adding that unfortunately she is no longer ten years old. I then presumed the girls still didn’t know? At which she hurriedly assured me that they didn’t, as if that made it better!

Little scratched his chins, and debated with himself whether it would be better to tell them now or leave it until later, deciding that it would have less effect now: they were already in a state of shock, it would probably lessen the impact. I was not sure, but could not see that piling later shocks upon them would be a good thing, so gave in, fetched them and sat them down. The false Miss Morgan, having resumed the hat, then got us all some tea, and once they got some down them, I explained. Or tried to. Had to order her to remove the d— hat, in the end. They just gaped. Finally little Parvati said: “But she’s quite young!”

“I thought Miss Morgan was quite old,” agreed Kamala—this all in the Bengalee dialect, you understand.

“No,” said Tiddy in the same tongue. “But I am grown up. I’m about eight years older than you, Kamala.”

They must have known she spoke it: after all, they had been communicating with her for months! But they just gaped, poor little dears.

“Up to you, now, Gil,” noted Little, going back into the bedroom.

“Yes,” said I as steadily as I might: “Tiddy baba is about eight years older than you, Kamala, and she lives in my English house. So you will both be able to come and live with her, as well as me.”

“But why did you dress up as Miss Morgan?” burst out little Parvati.

“I thought Ponsonby Sahib might be cross with me if I just came to see you, Parvati. Because English girls aren’t supposed to.”

To my huge relief this seemed to go over well with both of them, and they nodded seriously, Parvati then venturing, touching her own round cheek: “So you haven’t got—”

“No,” she agreed calmly. “It wasn’t a real birthmark.”

“Tiddy,” I burst out, “do not dare to say it was a dye: you showed no sign of it at all!”

“No, there’s no dye on your cheek,” agreed Kamala faintly. –Feeling the shock more than Parvati, I think, because she is older.

“No, it was a piece of cloth stuck on with paste. Nandinee and I did it. I thought if I looked bad enough people would not want to look too closely. They usually avoid looking at disfigurement, don’t they?”

“Off whom did you learn this lore?” I wondered wildly.

“Off you, of course, Ponsonby Sahib. That time you posed as a mali to keep watch on Mr Watson, you had a false birthmark on your face and a horrible burn mark on your arm, and you said that not only none of the feringhees looked you in the face, none of the indoor servants did either, and even the syces tended to look away.”

“True,” said I drily. “Though I don’t recollect mentioning it to you.”

“No, I was eavesdropping under the library table again.”

Parvati gasped and clapped a hand over her mouth, and I decided it was time to bring the conversation to a close. “Yes, well, you were a naughty little girl in those days, Tiddy, and though your intentions were good this time I don’t think you have improved all that much, have you? You may go home now. Where is the d— ayah?” Well, now! Nandinee was next door at the Ashbys’—they were still away but the servant had let her in. Fancy that. So a very chastened Nandinee Ayah was sent to fetch a tonga and I dispatched the both of them.

There was a lot to do: of course the funeral arrangements had to be made immediately. A pity that we could not have waited for Mrs Ashby to get down from Patapore, as she has always been so kind—if misguided in covering up for Tiddy. I did not get back to Ma Maison for a couple of days and when I did I had the girls with me—both in a quake of nerves. But George Little had been right in thinking we ought to tell them about Tiddy straight away, for their nervousness about coming to live in my English house was lessened by the knowledge that she would be there.

The next hurdle was introducing them to Josie and Mlle Dupont, but one good thing had come of Tiddy’s d— masquerade, for she had told them the whole. Mademoiselle was rather taken aback on meeting them—had thought they would be paler, doubtless—but Josie, to her great credit, appeared unmoved, said how pretty they both are, and offered to take them up to their rooms herself. And she was sure she had some dresses they might like. A trifle unfortunately she don’t bolo the baht, but Tiddy helpfully translated. So I went upstairs with the four of them and then left them to it.

Mademoiselle was in the downstairs salon when I came down and said very bravely: “I really do think you could have told us, Colonel.”

I sat down heavily. “Mlle Dupont, I’m not quite sure why I did not, to say truth! Well, I kept the marriage secret at first because I didn’t wish to lose my career. But later... I think,” I admitted, “it was Henry’s will.”

She frowned, very puzzled.

“The thing is, he knew,” said I heavily.

“Mais—mon Dieu! Mais alors—pourquoi?” she cried.

Why the terms of the will? Well, quite. I cannot tell you more than I said to her, Jarvis. Possibly it was a ploy: that is, since Henry knew I could not marry one of them, he knew that they would not, then, have disposable fortunes of a size to tempt the real scoundrels. Or possibly he was testing all our mettle? I really do not know.

Well, that is how things now stand, Jarvis. Josie at least is taken care of, and there is no fear that Welling will try to get out of the engagement because of my chee-chee daughters, in fact he turned up with pretty little trinkets for all four girls just this morning!

Voight wrote me a very kind and tactful note, so of course I wrote back thanking him and inviting him to call at any time, if he should care to. Did not think he would, but to my surprise he did. I wondered at first if he might be interested in Tiddy but, no: if anything he seems very taken by Kamala. He is too old for her, I suppose, but he is not yet forty and in these piping times of peace doubtless will not get another ship. His last has just been decommissioned—well, she was leaking like a sieve: if he was not a very good seaman he would never have managed to limp back all the way from Batavia and I think, though he is not one to boast of his exploits, before that all the way from New South Wales. Incidentally, claims it was the filthy water that Capt. Cook took on board at Batavia that nigh to finished off his crew on his first voyage—after getting them almost around the globe without even one case of scurvy, too! No, well, it is early days yet to be thinking of Voight for Kamala, but we shall see. He seems quite happy at the prospect of selling out and settling down on a small property in England. I own I would not like to see my little chicks settle too far from me.

As to Tiddy—well, don’t know whether to laugh or wring her neck, still, Jarvis. Have not really spoken to her this past fortnight. I’ll think it all over for a bit longer.

The rains had come and with them the usual relaxation of tension. Calcutta was a sea of mud but all was peaceful in the big white pillared house with the name that was Henry John Lucas’s private joke. Josie, Tiddy, Kamala and Parvati all seemed to be getting on famously, with Nandinee Ayah clucking over all four of them—in her element, apparently, though by Ponsonby’s calculations the woman was old enough to be their grandmother—no, well, perhaps that was a factor! In the better-off quarters umbrellas had sprouted like strange mushrooms, the two little girls being thrilled to be offered “English umbrellas” if they went outside, and all over the city those who were accustomed to the climate were muddy and drenched for at least half the day.

Robert Voight was calling about every other day. He did not say very much to Kamala but it was now clear he greatly admired her. She had finally nerved herself to say “Good morning, Commander Voight”, so it augured well. She was as yet far too young to marry, but they would see if the feelings endured on both sides. He was due to go home: a ship was leaving very soon and he would go and, he had already informed Ponsonby, give his final report to the Admiralty and hand in his papers. Then he would see his elderly mother and oldest brother in the country, and look about him for a pleasant little property—either a long leasehold or a purchase. And—with a twinkle in his eye—he rather fancied the Kentish coast, so if they should hear of any properties in that area, he’d be much obliged.

“Look,” said Tiddy in the wake of this visit, getting out the big atlas in the library, “this is a map of England, Kamala—in small, you see—and where we live at Tamasha would just look like a dot on it, just here; and this land here is all Kent.”

The girls peered. “But really it’s much bigger,” ventured Parvati.

“Yes, of course! Just like any picture, really! Well, your Papa painted that lovely picture of you and Kamala just the other day, did he not?”

“Yes, it was smaller than us, of course!” she said with her gurgling laugh.

“What are they saying?” asked Josie.

The girls’ English was coming along in leaps and bounds; Parvati turned and beamed at her. “I am saying that Papa painted small picture of us, but we are big!”

“I was explaining that a picture is always smaller, Josie,” said Tiddy.

“I see! Yes, a picture is always smaller,” she said kindly. “This—is—a picture—of England,” she said very carefully and slowly, pointing at the map.

“Yes, yes! A picture of England!” they cried.

“But it isn’t really that colour,” said Josie cautiously.

Tiddy had not ventured on that one: she swallowed.

“Um, maybe you’d better show them the map, I mean picture, of India, Tiddy,” Josie added lamely, as the girls were looking very puzzled.

Gamely Tiddy showed them the map of India. They saw: it was just a picture! And a mongoose was not really the colour of the drawing in their book!

Gamely Tiddy translated.

“No,” agreed Josie sunnily. “Did Tiddy draw it?’

They looked at one another dubiously. Finally Kamala ventured: “Tiddy did draw it. And Papa did draw it. After,” she ended uncertainly.

Josie nodded the golden curls hard. “I see! Tiddy can’t draw very well, so Ponsonby Sahib corrected it!”

Kamala and Parvati consulted together and agreed, with the head wobble: “Yes! Papa corrected it!”

“There!” said Josie pleasedly to her sister. “They understood! Aren’t they sweet?”

“Josie,” said Tiddy, trying not to laugh, “they are not babies, you know. They understand quite a lot we say.”

“Of course!” she beamed. “Well, Kent is colder than India, of course. But the house is very warm. I think you’ll like it!”

Happily Kamala and Parvati agreed they would.

Ponsonby was just outside, sitting in a chair on the verandah. Beyond the pillars the rain was streaming down again, but of course it was not cold. He had not meant to eavesdrop but the temptation had been irresistible. He stretched his legs out and smiled.

Josie had taken Kamala and Parvati upstairs in order to try on all their mother’s jewellery—on all three of them, one presumed, precisely how they would communicate being best left to the gods to decide—though doubtless it would do all three of ’em good! And presumably that left Tiddy in the library. Ponsonby made a face. He’d better speak to her: it was no use putting it off any longer.

He went in very slowly. Uh—damnation! “Where is she?” he said crossly.

“Here, Ponsonby Sahib,” said a very small voice from the nether regions.

What? He lifted the big fringed cloth that usually protected the huge mahogany table from the sun—not that they’d seen it today. “Tiddy, what on earth?”

“I just felt like it,” said Tiddy, still in the small voice. “I was thinking of Papa... And the old days, I suppose.”

He just looked at her limply.

Tiddy tried to smile and failed. “You brought us all a packet of jullerbees when you came back from the office yesterday... It was just like the old days!” she gulped. A big tear ran down her cheek.

“Oh, Hell,” said Ponsonby under his breath. He knelt. “Come out of there, Tiddy baba. I am not cross with you, I promise, and—and I’ll do my best to make it always like the old days,” he said, with tears in his own eyes.

“You—can’t—Ponsonby—Sahib!” she gasped, bursting into sobs.

At this he simply crawled in beside her and got both arms round her.

Tiddy sobbed into his chest for quite some time. Mercifully, no helpful persons turned up with offers of unrequested refreshment.

“Better?” he said at last.

“No,” said Tiddy in a stifled voice. “It can’t be. I love you, Ponsonby Sahib.”

“I love you, too, Tiddy baba,” he said, hugging her strongly.

“No,” she gulped. “I mean, not like that! I mean, I always have, but... It doesn't matter.”

“Yes, it does. –No, just listen,” he said as she tried to pull away. “I’m much too old for you, but—well, coming back to India makes that sort of consideration seem... not absurd, exactly. More irrelevant. One never knows what the next turn of the wheel may bring, after all.”

“I’ve always thought that,” ventured Tiddy dubiously.

“Mm: you grew up in the country,” he murmured. “And—well, I don’t know, really, Tiddy. I cannot say I’ve had a change of feeling, exactly, because I’ve loved you all your life. It’s got deeper, I suppose, and I don’t want you for my daughter—no, that’s wrong. Never really thought of you as a daughter, even when you were little. Uh—think Henry said at one stage that you considered yourself my faithful lieutenant or some such. It was a bit like that for me, too... Well, one cannot analyse these things, really. I always felt very strongly,” he said slowly, frowning over it, “that you were a person in your own right.”

“Did you?” said Tiddy uncertainly, looking up at him.

“Mm.” He stared into space, not registering that part of the space, beyond the fringe of the tablecloth, was occupied by the bottom of the door to the passageway, just slightly ajar. “When I saw you again at Tamasha after all those years, at first I thought it was just the same, and then I realized it was different. Well—think I was in the same case as Robert Voight, really,” he said with the ghost of a smile. “Had to wait for you to grow up a bit, mm?”

Tiddy swallowed. “Did you?”

“Uh-huh. Then, I could not offer, since I was married already, and—well, I had a strong feeling that dashed Henry’s will was calculated precisely to prevent me from offering, though I’m d— if I can figure out why!”

“Papa had a very devious mind,” said Tiddy slowly.

“He most certainly did!” he said with feeling.

“Much more so than you: in your place he would have guessed I was Miss Morgan, I think. I—I’m very sorry about that, Ponsonby Sahib. I have thought about why I did it, but I—I don’t really know!” Tears threatened again: she sniffed hard.

“I thought it might be like that. Don’t bawl again, Tiddy. I think it was partly for the adventure, wasn’t it?”

“Yes,” she said in a small voice.

“Aye... Well, can’t blame you for that. One last fling, kind of thing? When d— Moriarty took over, and forbade me to go on with me spying, I went straight out and told K.K. that I was up for a jaunt up to the Frontier with him—he’d heard a rumour that the Russians were plotting something up there, you see.”

“Ponsonby Sahib, one hears that rumour all the time!”

“I know,” he said, making a rueful face. “My plan was, get up there as one of K.K.’s men with the kafilah, cosy up to the most likely-looking villains—well, you know the sort of thing. He persuaded me that Moriarty would have my neck for desertion: talked me out of it.”

“Hurray for Mr Khan!” said Tiddy with a relieved laugh.

“Aye—always had his head screwed on. But you see? Wanted a last fling: the excitement of it.”

“Yes, I see. You felt the same as me.”

“Aye. Uh—I have to say this, though, Tiddy: I was very hurt that you’d deceived me.”

After a moment Tiddy said: “Yes. I’m sorry. The thing is, I was very hurt that you hadn’t told me about your marriage. Um, I don’t mean the fact that you weren’t free; I mean that you could keep such a big secret—”

“Yes. Hush,” he said, hugging her tight. “Like dashed Little says, faults on both sides.”

“Yes,” said Tiddy with a sigh, leaning into his embrace.

They stayed like that for quite a long time, neither moving.

Finally Gil Ponsonby said: “You’d better marry me. Damn the age difference, damn the fortune—we’ll put it in trust for the children or something, I don’t care. And damn what Calcutta society may think!”

“Yes,” said Tiddy in strangled tones into his chest. “If you really want to.”

“Of course I do! I’m not stupid enough to say it if I don’t mean it! Er, there is just one thing,” he said as she looked up at him, her eyes shining. “The age difference.”

“It doesn’t matter!”

“No, it doesn’t. But to pretend it ain’t there would be absurd. What I mean is,” he said, his mouth twitching, “I’m afraid you will always be Tiddy baba to me—malum?”

“Oh, good!” said Tiddy in huge relief. “Because you’ll always be Ponsonby Sahib to me!”

With that—though that just slightly open door had now registered—Gil kissed her thoroughly. And managed almost to ignore the muffled rejoicing that arose in the passage.

Endnote by Katy Widdop

And so they all lived happily ever after. Well, as much as is humanly possible. There were some deaths in infancy—this was the 19th century, after all—and Antoinette’s and James Thomas’s eldest son died tragically in the Boer War. But Julie and Sally between them have drawn up a huge family tree and it’s obvious the Ponsonbys and the Widdops, as well the Thomases, all did pretty well. Madeleine Thomas did marry David Widdop, Tess’s grandson—if she hadn’t done, none of us would be here! Tamasha burned down in the 1930s, as I mentioned earlier, but Julie’s discovered that that branch of the family didn’t die out as we thought, but emigrated to Canada, good on them! And our branch of the Widdops, of course, ended up in Australia via India and the jolly old Empire. Sally tracked down some distant relations who still live in England: he’s a solicitor. I won’t mention where, because when she wrote them a lovely letter they didn’t want to know! What the Hell did they imagine we were after? Their flaming family fortune? Don’t think English solicitors have those, do they? Sally was very bitter, poor girl, God knows what she’d been expecting, and said that any form of enterprise or pioneering spirit that had once existed in Britain had vanished to the colonies with all of us immigrants! Dunno that I’d argue with that, actually. Not that I’m claiming yours truly’s got any of either. But heck! What about natural curiosity?

You want to know about Ponsonby Sahib’s little daughters? Well, they did go to England: he and Tiddy married in January 1832 and their eldest son, John, was born at Ma Maison in October that year. Then they all went back to England for a while, and their second son, Henry, was born at Tamasha. As to the girls: well, here is what Madeleine Thomas says in her final letter of the Tamasha summer:

… Alas, our halcyon summer is over, the leaves are turning, and the house party at Tamasha has broken up, with the Standish children returning to their parents’ home and Mrs Tess and Mrs Tonie, who as you know now live together, departing to the little dower house on the Widdops’ property. Little Matt is staying on, however, and his governess has now come. His mother, Mrs John Ponsonby, is extremely fashionable, and as they are staying in town for the autumn season, with the intention of spending Christmas in Paris, they were quite happy for him to stay with his grandparents. Dear “Tiddy baba” v. pleased to have him, tho’ I have to say it, extremely annoyed with Mrs John. The child has scarce laid eyes on his parents all year. Little Gil baba of course also stays on, as Major Jarvis Ponsonby and his wife are in India with the regiment, and she does not care to expose her little chick to the climate, having already lost two babes to the dreadful tropical diseases that ravage the sub-continent. I must say, it makes one think twice about going out there, does it not? Tho’ Antoinette seems as keen as ever. I do hope that Mr Widdop will keep safe and well, and pray for him every night.

The great excitement this week was a visit, well rugged up, to Cmmdr. & Mrs Voight’s house on the coast! It is not so very far, of course, and certainly not the first time the little boys have visited, but were in a state of huge excitement, for their dear “Aunty Kammy” as they call kind Mrs V., has always the most delicious Indian treats for them! And if very good may be allowed to peer through the Commander’s very own spy-glass! When we got there we discovered that Mrs V.’s sister, Mrs Kenneth Dalziel, and her kindly husband were there, too: dear Mrs Col. Ponsonby most thrilled to see both her step-daughters at the same time. Ponsonby Sahib himself did not accompany us, as the wind was so very chill, but they said they would come back with us. The Cmmdr. very frail now, but his spirits still bright, I am glad to say. The children’s “Aunty Parvy” so very pretty still, tho’ I dare say she is Mamma’s age, and her daughters, Theresa and Josephine (whom they call “Pretty”, charming, is it not?) now both quite grown, Theresa already out, and little Pretty, tho’ they do not lead a very fashionable life, as he is but a country vicar or whatever they call it in Scotland, will attend her first grown-up party next year. She is still very artless and confided to self & A. that their distant cousin Gordon Dalziel has been paying marked attentions to Theresa, and the Duke of L. not best pleased, as of course he is the heir, and they are but poor relations in comparison—and, then, one must admit there is the mixed blood. Oh, dear! And it comes out so pretty, too, I am sure I cannot see why the crusty old thing should object. And I must admit, tho’ not to my personal taste, that young Mr Voight is the handsomest thing! Huge, liquid dark eyes, a creamy complexion, and the straightest nose! Little Susannah Holden from their local vicarage was there with her parents to dine and could not take her eyes off him! We stayed for 3 days in all, the most delightful time, and then the Dalziels together with Mrs Voight came back to Tamasha. I was pressed to stay at the house but Mamma said firmly that it was high time I came home, for they have scarce laid eyes on me these last 4 months. A gross exaggeration.

And personally I do not see why Theresa D., who is the loveliest thing, with the sweetest temperament, very like her mother and aunt, should not marry a silly old duke’s heir and it is all stupid conventions, and if James and Antoinette should marry and go out to India I have quite decided, I shall go, too!

Well, Madeleine did eventually go out to India, not quite as she envisaged, but with her husband, and she and pleasant David Widdop had quite a large family. However, by the late 1890s, when Antoinette was writing what was intended to be the definitive family history, she had died: she would probably not yet have been fifty, so it’s no wonder Antoinette sounds upset about it, in her preface.

Ponsonby Sahib’s own family seems have travelled back and forth between Tamasha and Ma Maison quite regularly, and they were in India in 1840, which was the year that Ponsonby Sahib did a detailed pencil drawing (which I think was a joke, though Julie disputes this fiercely), based partly on an earlier watercolour portrait of Kamala and Parvati wearing their mother’s jewellery, which he called “Mrs Gilbert Ponsonby in Indian dress with her step-daughters, Kamala and Parvati”. (It must be a joke: Tiddy, at the far right, has got her face darkened!)

By this time Tiddy was thirty and Kamala was twenty-two. It was two years before, when she turned twenty, that her father allowed her to marry Commander Voight. Presumably he went out to India with them, that trip.

And Parvati’s husband was a relation of the Dalziels who were Josie’s friends in Calcutta. Julie and Sally had an argument over whether one of her daughters did eventually marry the duke of whatever’s heir (all right, Julie, the Duke of Lochailsh’s heir and if that’s not how you spell it I don’t care!). Julie won. No, she didn’t marry him. Fancy that.

No, well, life was far from perfect, never mind that Madeleine Thomas uses the word “halcyon” about sixteen hundred times in her letters. And very few families were as unprejudiced about mixed marriages as the Ponsonbys and Widdops, by the middle of the 19th century—attitudes hardened throughout the century. But as I say, the family from Tamasha did all live happily ever after, as far as that’s possible!

Later. Post-Shiraz.

Julie’s read it all through thoroughly and she says I have to say something about us. Because I went on and on about us all and Jack Cooper, apparently. But gee, there’s nothing to say. Jack Cooper and me? Don’t be funny, gorgeous long-legged types like him—born to be lords of creation, yep—don’t look twice at eccentric, dumpy little untidy women like Katy Widdop, that can’t even run a house properly and do the wifely-support thing. Let alone run their lives for them, which most of them, when you think about it, seem to want, don’t they? Go on, name one married woman who doesn’t... See?

There were compliments all round and lovely bouquets for all of us—and of course Cassie laid on the most elaborate farewell dinner for him, more Indian recipes from Our India Days. Well, there were only half a dozen of us: Julie and Cassie and me, plus Jack, plus Charles and Sally, so it wasn’t nearly as huge as a real Indian feast, say the ones they lay on for weddings. Unfortunately Bob and Terri Darling couldn’t make it: had to go interstate for a golden wedding on her side. We invited good old Uncle Don and Aunty Jen but they thought they wouldn’t: “Sounds lovely, but a bit too spicy for us, dear.” So like I say, there were just the six of us and even Cassie didn’t lay on more than eight dishes for the main course.

What were they? Well, according to her, “Special Lamb Kormer Curry”, “Prawns with Saag”, “Saffron Rice”, “Goodie Curry” (zucchini), “Hot Begoon Curry” (aubergines), “Samosahs for a Special Occasion”, “Curd with Bananas” (that’s a yoghurt raita), “Indian Salad”, and for dessert, “Goolab Jamoons”; and a mint drink for those that fancied it. No, well, six main dishes plus a salad plus a raita. Here are the recipes. Cassie reckons they’re not hard. (Possibly not, if you’re a cook.)

The meat curry had guess what? Lashings of butter and cream! According to Cassie it was the very one mentioned in one of Antoinette’s later letters as having been passed on to her from the great-aunts as the very one served up for Ponsonby Sahib’s and Tiddy’s wedding! No-one could prove it wasn’t and for a miracle even Julie didn’t argue. Or tell her that she’d used “the very one” twice in one sentence.

Special Lamb Kormer Curry

This delicately rich dish with cream & ground almonds would be served for a feast, perhaps a wedding. Kormer [korma or qorma] is an Indian method of braising. The meat must not scorch.

Slice 1/4 lb [125 g] of onions & a piece of fresh ginger (about 1/2 dessertspoonful) & fry in 3 tablespoonfuls of butter until light brown. Put aside, straining any butter & reserving. Cut 2 lbs. [1 kg] of lamb into cubes & mix well with 3/4 tablespoonsful of turmerick, a further 1/4 lb. of onions, sliced & crushed, & a further 1/2 dessertspoonful of sliced ginger. From 1/2 pt. [300 ml] curd [yoghurt] add enough to moisten. Now heat the butter, adding more if necessary, & fry the meat mixture for 3 minutes. Add the remaining curd & cook until the meat is dry. Continue to fry, covered, with little sprinklings of water, till tender.

Now take 3 oz. [75 g] almond meal with 1 gill [140 ml] of cream, a further 3/4 tablespoonful of turmerick, 2 bay leaves and 1/4 teaspoonful of chilli powder. Add the reserved onions, mix all well, & pour over. Cook gently for 12 minutes. Slivered almonds may be added to garnish. Sufficient to serve 4-6.

It was totally delicious and more-ish and at the time I did manage to stop thinking about cholesterol and my waistline, not to mention the hips.

Some might have thought it was strange to have a prawn dish as well as a meat dish in the same course but Cassie claimed it wasn’t, in India, and at the planning stage started hauling out the books to prove it, so I shut up. Anyway, South Australians always serve up prawns for special occasions. I’d have said from the look on his face that Jack C. had never encountered the combo before, and certainly not prawns with English spinach mixed into them, but he ate it and praised it, all right.

Prawns with Saag

This is a rather dry curry from Bengal. Spinach may be substituted for the saag [mustard leaves]. Discarding hard stalks, chop 2 lbs. [1 kg] saag leaves coarsely & boil for 5 minutes in 1 pt. [600 ml] of water. Quickly drain. Heat 3 ozs.[about 75 g] ghee or mustard oil, & fry 1 finely sliced onion & clove of garlic until softened. Add spices in the following quantities: a 2-inch [5 cm] stick of cinnamon, 1 teaspoonful each of jeeruh [cumin] powder & ground coriander powder, 1/2 teaspoonful of turmerick, 2 teaspoonsful of chilli powder, & 1 of black pepper. (Less of the last 2 to suit English palates if preferred.) Cook for 2 minutes. Add 4 fl. ozs. [125 ml] of puréed tomato with 1 teaspoonful of honey & stir, cooking, for a minute. Next add the saag with 1 teaspoonful of salt. Stir all well & add 12 oz. of peeled & cleaned prawns. Cook, stirring with care, until well heated through. Sprinkle in 1 teaspoonful of your good Indian spice mix [garam masala] & cook gently for 5 minutes more.

******

A Good Indian Spice Mix

Take 3 measures each of elaychee [cardamom] & cinnamon to 1 each of cloves & jeeruh [cumin], with 1/4 each of mace & nutmeg. Best made up in 2 oz. [about 50 g], no more. Grind together & pass through a fine sieve. Store in an airtight bottle. It keeps well for a fortnight but should not be kept longer, else its aroma fades.

Actually everybody ate it, though possibly not all appreciated the spinach. And see, the mixture was authentic. Well, yeah, though Cassie admitted that in India it wouldn’t be English spinach at all, it’d be mustard greens. Or they’ve got another green vegetable they sometimes use instead but as she failed to come up with an English name—

She did a rice thingo instead of the naan that are my favourite—a special rice thingo.

Saffron Rice

Plain rice may be simply boiled with a little saffron or turmerick added to colour, with often a little ghee or melted butter added when done. But for a more festive occasion, this richer dish will appeal.

Your lb. [450 g] of rice must be well washed & drained. Put 4 ozs. [125 g] of ghee to your heavy, lidded pan, & fry an onion, finely sliced, till soft. It must not brown. To this add 1 clove of garlic, thinly sliced, with 1 teaspoonful each of turmerick & whole jeeruh [cumin] seeds. Mix it well & fry gently for 2 minutes. Next add the rice, stirring well. To this put 1/2 teaspoonful of saffron soaked in a cupful of boiling water. Add 1 teaspoonful of salt, cover all with more boiling water & put on its lid. Cook very gently till the water is all absorbed.

[This is somewhat trickier than the recipe implies. To cook perfect saffron rice, after the spices have been fried transfer everything to a rice cooker and let it cook it for you. Don’t be tempted to use less ghee/butter, as this is supposed to be a rich-tasting dish. It serves 4-6. –C.B.]

It was yellow but it wasn’t just saffron because blah, blah, dunno. I copped a gander at the recipe when she was planning the spread: how much butter? It still sounded appalling even when she’d translated it into grammes. Yeah, all right, Cassie, just for once. And yeah, it was yummy.

The veggies were nice, one zucchini thingo and one aubergine.

Goodie Curry

A delicately spiced dish. Take a nice young marrow or courgettes to a weight of 2 lbs [1 kg], or a little more. If very young it does not require peeling. Cut into cubes & sprinkle with a teaspoonful of salt. Fry a thinly sliced onion in 4 ozs. [125 g] ghee until soft & golden. Add to this 1/2 teaspoonful each of yr. good Indian spice mixture [garam masala], chilli powder & turmerick. Stir well. Put in the vegetable pieces & turn gently to coat well. Simmer gently, covered, for 10 minutes. They must retain their shape. A little water may be added if necessary.

Well, yeah, loads more butter. Mind you, there were six of us, but all the same… True, it made the zucchini taste actually interesting, and it was a nice change from the ratatouille that Cassie often serves up. Jack reckoned he’d never had a zucchini curry before (he called them courgettes, like in the recipe, must be a Pommy thing). Wonderfully delicate and complemented the lamb, was the word. Well, he lapped it up, so maybe it wasn’t a polite Pommy lie.

She didn’t do the very hot version of the aubergine one, thank goodness. One time she did, and none of us could get through it except Charles, and he had to drank three cans of Foster’s with it.

Hot Begoon Curry

Firstly, pour boiling water over a lump of immalee [tamarind] & soak for 2 hours. Strain the water off, squeezing pulp well. Discard seeds & pulp débris.

Now cut up your begoons [aubergine], about 1 1/2 lbs [675 g]. Fry gently in ghee or oil for a little & put aside. Fry 1 large onion, sliced, until soft. Add 2 cloves garlic, sliced, together with 1 1/2 teaspoonsful of chilli powder (less to suit English palates, if preferred), 2 teaspoonsful each of coriander powder, turmerick & mustard seeds. Put in a little fresh cocoanut, sliced, 3-4 ozs. [100-125 g] suffice, with 2 bay leaves. Add the immalee water & the begoon with 2 teaspoonsful of honey & 1 of salt. Cover pan tightly & simmer for 5 minutes. Stir in 1 teaspoonful of yr. good spice mix [garam masala] with, if liked hot, 2 chopped green chillies. Cook another 10 minutes until the vegetable is done.

This version was much nicer than the very hot one. Left the actual chillies out, was that it? Think so.

I'd have said the samosas were overkill, especially since they were meat ones, but this was a special occasion. Yeah, okay.

Samosahs for a Special Occasion

Make a plain firm pastry dough with 2 tablespoonsful of butter to 2 cups of flour & 5 tablespoonsful of sour milk [yoghurt]. Shape into small balls, roll out perfectly round & very thin, about 5 inches [13 cm] across. Cut in half & shape each semicircle into a cone.

Put in the following stuffing: For 1 lb [450 g] of minced meat, take 2 green peppers [capsicums]. Fry them, sliced into thin strips, until they soften. Put aside & fry 1 good onion, finely sliced. When soft add 1 teaspoonful each of cinnamon, cayenne, jeeruh [cumin], & yr. good Indian spice mixture [garam masala], with 2 each of salt & black pepper. Less cayenne if preferred. Stir well & cook till they release the odours, it will be about 2 minutes. Then put in yr. minced meat, stirring till browned. Put in yr. cooked peppers & cook for 2 minutes more. It may also be eaten as a curry.

To complete the samosahs, fold over the mouth of the cone to close, using a touch of water to fasten down safely. Fry in deep oil till crisp.

Indian Salad

If you have it, finely grated fresh ginger makes yr. best dressing. To it put lemon or lime juice, a little vinegar, & a good amount of ground coriander seeds, chilli powder, salt & black pepper. Sprinkle your lettuce leaves with salt & black pepper, & chop coarsely. Mix with chopped sweet onion, & layer with sliced tomatoes & cucumber in yr. salad bowl. When ready to serve it, pour on the dressing.

It’s almost impossible to get sweet onions in SA, except very occasionally they have these white ones with long, soft green stems that they call spring onions, but they’re not, they’re full-sized ones, and they’re yummy, very sweet, only Cassie couldn’t find any, so she used ordinary spring onions instead: not too much, as she didn’t want them to dominate the dish. I left my bits anyway, any raw onion (except those soft green-stemmed ones) and I’ll be tasting it for the next 24 hours.

The raita was banana, I usually find it too sweet but as Charles does too and both he and Sally, not to mention the whole of their generation, won’t go near a banana that’s got even one brown spot on it, she used really firm ones and added some lemon juice. Not bad.

Curd with Bananas

A mild, refreshing side dish which may be adjusted to suit your taste. Beat 2 cups of curd [yoghurt] & 1/2 teaspoonful each of salt and black pepper till smooth. Add 3 firm bananas, sliced, sprinkled with the juice of 1/2 lemon. Two or three tablespoonsful of desiccated cocoanut may then be added. If liked, stir in some chopped dhania leaves [coriander] & green chillies if you wish it hot. Garnish with a little more of the same & extra cocoanut if liked. A sprinkling of paprika is often added.

Officially there was this mint stuff to drink, only Jack brought a bottle of fizz and Charles nicked a ditto from his bloody dad’s cellar. (Not what he left behind, his current cellar, heh, heh.) They washed down the curry quite well. Sally doesn’t drink alcohol much, she reckoned she liked the mint thingo. Don’t think Cassie mentioned she’d added food colouring—Sally doesn’t approve of food additives.

To Make a Refreshing Summer Mint Drink

To 1 1/2 pints (900 ml) of water measure 1/2 pt. (300 ml) of fresh mint leaves. Chop coarsely & mix with 1 teaspoonful of aniseed, if to your taste. Put this to a large bowl. Boil the water with 1/2 lb. of clean sugar, stirring until dissolved. Some like to add 1 inch [2 cm] of stick of cinnamon, the powder will not do. Now pour all over the mint. Cover it. It must infuse 2 hours. Strain, boil again & reduce by half to finish. It is served cold with cold water as any sherbet. Fresh mint leaves are a pleasant addition.

[2-3 drops of green food colouring are added in modern versions after it has infused. Serve over ice. -C.B.]

The pudding was yummy. Those little round balls. Um, well, one variety, she’s got several. Not the ones with the funny flour that she claims Ponsonby Sahib liked and we’ve mentioned that, Katy! Have we? If she says so. (Pea flour? Doesn’t sound likely to me. However.) These were sitting in a syrup flavoured with rosewater. Ambrosial, is the only word.

Goolab Jamoons

First, boil down 1 qt. fresh milk until well thickened.* Mix together with 1 tablespoonful of plain or rice flour & 1 of baking powder to make a soft, stiff dough. Leave it to stand for an hour. Then shape into walnut-sized balls. Heat ghee [or oil] for deep-frying and slowly fry the balls till golden. It must not be too hot or they will not cook all through. Prepare a thin syrup of 1 cup of sugar to 2 of water & to this add 2 tablespoonsful of rose water (or less if to the English taste). Elaychee [cardamom] pods or small pieces of cinnamon may be added. Lay the jamoons in the hot syrup & let them soak for a few hours. Some like them with a nut, elaychee seeds or sugar lump inserted in the jamoon when shaping.

* [Substitute 250 g. (8 oz.) full-cream milk powder & 10-12 tablesp milk –C.B.]

It was the sort of meal that makes you feel you may never eat again for the next fortnight. Or need to.

And after that, gee! Jack vanished back to England and his real life. Yep, the colonial thing was in there, too. Nothing about the Antipodes is really real, to a dyed-in-the-wool Brit. So how could he possibly have taken me seriously, even without the dumpy, eccentric, not-housewifely factor?

Oh, well. That’s life, isn’t it?

No comments:

Post a Comment